The daughter of diplomats, Jane Bow grew up in Canada, in the U.S., in fascist Spain, in England and in communist Czechoslovakia. The French and British schools she attended could have come out of a Charles Dickens novel and her teenage holidays were spent behind the Iron Curtain. This background has given her insights that inform her history-based fiction.

Cally’s Way, Jane’s third novel, was published by Iguana Books in 2014. Set in Crete, it interweaves the story of 25-year old Cally, a Canadian business graduate, with that of her grandmother Callisto who was a runner in the Cretan Resistance during the Germans’ brutal World War II occupation.

Kirkus called Cally’s Way “accomplished, lyrical … romantic but toughminded.” The novel reached #2 on an Edmonton bestseller list last September, and Jane received Canada Council funding to present it to the U.K.’s Folkestone Book Festival in November.

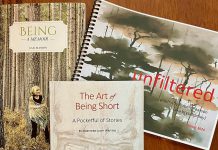

Jane’s second novel, The Oak Island Affair, was a 2008 Indie Book Award finalist. Dead And Living, published by Mercury Press, was shortlisted for an Arthur Ellis Award, and selected for a university course in 2002.

Jane now lives on the edge of a forest in Peterborough, Ontario.

Cally’s Way interweaves the story of 25-year old Cally with that of her grandmother Callisto, who was a runner in the Cretan Resistance during World War II. The excerpt below comes from the World War II story.

Cally’s Way is available in print locally at Chapters Peterborough (873 Lansdowne St. W., Peterborough, 705-740-2272) and Happenstance Books & Yarns (44 Queen St, Lakefield, 705-652-7535) and online in print and ebook editions at Barnes & Noble, Amazon, as a Kobo ebook, and for iOS devices on iTunes.

An excerpt from Cally’s Way (Iguana Books, 2014)

Frogs are gossiping in a stone cistern beside a vegetable patch outside the village of Myrthios. Crouched under some olive trees off the path that cuts across the mountainside, Callisto holds her breath. Around her, sharp-shaped olive leaves are whispering in the darkness. Her eyes dart between the trees and the low stone walls that terrace this Cretan mountainside, and the great spiny aloe ghosts, searching for an outline, a movement, the grey glint of a rifle. Her ears are tuned to pick up even the scratch of a beetle. Her run up behind the village of Sellia, nestled on the next mountain, then down into the valley and up again through this olive grove has taken too long, but there is no wind tonight, at least. Down at the far end of the bay, the rocky outcropping known as the Dragon’s Head lies sleeping under a tipped crescent moon.

One of the trees, its ancient trunk crooked into a right angle, has the silhouette shape of a beard below the moon smile. Above it, she picks out stars for the nose, eyes: Zeus.

Please, please, great god, I know I’m not supposed to talk to you. The priest says that appealing to you will take me straight to Hell but the way I see it you have been here the longest so please, great Zeus, will you help the people of Agalini tonight?

Two mountains farther down the coast, parents and grandparents will be moving quickly now on the news she has passed to the next runner. She thinks of them shaking their children awake, packing yesterday’s bread, some sheep’s cheese, and whatever clothing they can carry, the women binding their babies to their breasts, the men hoisting toddlers onto their shoulders for the trek up into the safety of the wild mountain heights.

Please make them hurry.

A new sound, faint, rhythmic, tattoos the air behind the frogs. Callisto slides down behind the Zeus tree. The frog-talk stops.

Boots, more than one set, crunching. Six German soldiers come down the path toward her. They must have come through the Kourtaliotis Gorge, the opening in the mountains behind this part of the south coast, where she is headed now.

They are so close now she tastes the dust they are raising, smells the acrid metal of their guns. The Nazis think the village of Myrthios is friendly, but Uncle’s resistance network has friends there, and Callisto knows that up its cluster of alleys people will be lying rigid in their beds, praying that the stomping does not stop. She presses her cheek against the Zeus tree’s rough bark, closes her eyes, and prays not to move.

The boots beat the path, impressing upon even the ground that they own it, that they have a God-given right to drop out of the sky, take this island, and murder all those who would stand against them. If only she had a weapon or a bottle filled with kerosene, like the little boys in Agalini. They must have heard about the boys north of the gorge who had filled three bottles with gasoline siphoned out of a German Jeep. The next time a Nazi drove into their village the boys had lit a rag tucked into one of the bottles, then rolled all three of them under his vehicle. Waiting around the corner, giggling into their hands, they had had no idea that the bottles, exploding, would turn the jeep into a bomb, tearing the bodies of both the officer and his driver into fragments and tossing them into the air. Those boys are still in hiding, on the run, heroes. This must be why some of Agalini’s little boys have followed their lead, tossing their bottle of kerosene through the front door of the house the Nazis had commandeered, aiming for the hearth while the soldiers relaxed over dinner. No one has turned in the little Agalini boys either. And that was why tonight news had reached Uncle Vasilios that tomorrow the Nazis will deliver retribution to Agalini.

Callisto had come home from the sheep pasture to hear voices rising in the storeroom off the courtyard. Someone must be sent, tonight, to warn the villagers.

She opened the storeroom door.

“Uncle?”

“Go inside, girl.”

“I could run to Agalini, Uncle.”

“You!” A jet of anger, frightening. Only a month had passed since Georgios had made the mistake of scrambling up the cliff, not wanting to drop down below the path, out of sight, because there were Allied soldiers down there, hidden in a cave by the river.

Callisto stood her ground.

“I can run, Uncle. Out in the pastures I have been practicing both speed and distance and I am faster than any boy you will find. Just ask the local sheep thieves.”

“A girl running alone? Absolutely not.”

The other men’s faces stayed blank in the candlelight, not to intrude.

“In the middle of the night in the mountains, who will see me? I can do this, Uncle. Please, let me make my parents proud.”

And there was no one else.