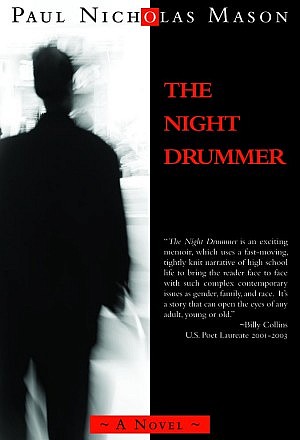

Paul Nicholas Mason is a prize-winning playwright and author of Battered Soles and The Red Dress.

His previous works have been nominated for the Stephen Leacock and ReLit Awards.

Born in London, England, Paul was raised in Rhodesia, British Columbia and Ontario. He is a graduate of Trent University in Peterborough and Queen’s University in Kingston. He lives in Peterborough.

The Night Drummer is the story of two teenage friends — white, middle-class Peter Ellis, and Otis James, a native boy adopted by an older evangelical Christian couple. Peter and Otis grow up in small town Ontario in the 1970s, and the novel follows them through their high school years when both confront challenges that require them to decide who they are and who they want to be — decisions that will have profound consequences not only for themselves, but for their friends and family.

The Night Drummer will be available in bookstores and online in the spring of 2015. You can order online at Chapters Indigo or Amazon.

For more information, visit www.nonpublishing.com.

An excerpt from The Night Drummer by Paul Nicholas Mason (Now or Never Publishing, 2015)

Eventually a male voice summoned us to table. When we came down the stairs, our hands washed, I was greeted by Mr. Jones. He would have been of average height, were he not bent over a little. His hair was thin and greying, and he, like his wife, seemed older than he really was—and he was certainly older than her to begin with. “Welcome, Peter,” he said. “It’s good that you’re able to break bread with us.”

“It’s good to meet you, sir,” I said.

We followed him into the dining room, and found that Mrs. James had prepared a chicken and vegetable stew, served with a loaf of pre-sliced white bread. “Your dinner looks wonderful, Mother,” said Mr. James. I was briefly puzzled by his calling her Mother, but then realized it must be a formal endearment. We sat down.

“Grace,” said Mr. James, and I bowed my head and closed my eyes; I’m sure the others did, too. “Lord,” said Mr. James, “we thank you that our day’s work is mostly done, that there is bread and stew for us to share, and that Peter is able to visit with us this evening. And we ask your blessing on us all, and on all those whom we love.”

“Amen,” I said, and I raised my head and opened my eyes, only to find that Mrs. James still had her eyes screwed tightly shut. I closed mine again quickly, too.

“And Lord,” she said, her voice sounding slightly hysterical, “we pray that you will bring Peter to Jesus even as you have brought Otis out of the darkness of his heathen past. And we pray that you will work your mysterious ways in the lives of all your children, so that they may see the light of your merciful kingdom, and so escape the final judgment and the lake of everlasting fire. Amen, I say, amen.”

“Amen,” said Mr. James and Otis; I confess that I was too startled to join in. I’d never heard a prayer like that in my life. I opened my eyes, and found that Otis was looking at me. He smiled slightly.

“Would you like some bread, Peter?” said Mr. James. I nodded and took a slice.

“We’re glad that Otis has found such a good friend,” said Mrs. James, her voice sounding a shade more normal.

“I’m glad he moved here,” I said, my tongue untied. “I mean, I’m glad you all moved here.”

“We’re happy here, aren’t we, Mother?” said Mr. James. “It’s much quieter than Toronto.”

“And I like my school,” said Otis.

“There are so many wicked people in this world,” said Mrs. James. “We couldn’t be sure how Otis would be received. I prayed that he would find a friend.”

“Otis is very popular at school,” I said. This wasn’t altogether true, but I felt it might comfort her. “So many wicked people,” repeated Mrs. James, as if I hadn’t spoken at all. “So many wicked, wicked creatures.” Her eyes were glistening, and I realized suddenly that she was crying.

“There, there, Mother,” said Mr. James gently.

“There are nice people, too, Mom,” said Otis.

Mrs. James sobbed once, then breathed in very deeply. “Eat your stew,” she said, in a strangled voice. “Eat your stew, and don’t worry about me. I just feel the weight of the world’s wickedness so powerfully. It bears down on my shoulders ’til I can hardly think straight.”

So we ate our stew, which was, frankly, very plain. There was plenty of it, however, and as Otis’s mother now fell silent, and as Mr. James drew me out with a few gentle questions, my teenage appetite eventually prevailed, and I gladly accepted a second helping when Mr. James offered it. Apart from the odd snuffle, Mrs. James made no further comment for the rest of the meal.