A parasitic tapeworm that can cause a potentially fatal disease in humans has been reported in a dog in Peterborough for the first time.

Sherbrooke Heights Animal Hospital confirmed a canine patient has tested positive for Echinococcus multilocularis (E. multilocularis), a tiny tapeworm carried in the small intestines of canids like coyotes, foxes, wolves, and dogs.

In both domestic dogs and humans, the parasite can cause a potentially fatal disease called alveolar echinococcosis.

“There’s a specialized fecal test specifically for echinococcosis because that’s something we regularly keep an ear out for,” says Dr. Kristen Harton, a veterinarian at Sherbrooke Heights Animal Hospital. “There are lots of people that do routine fecal screening through their vet, but this wouldn’t be picked up on those.”

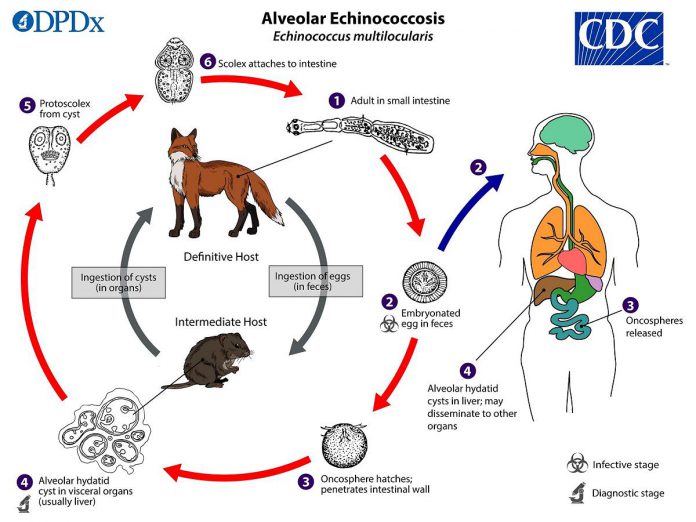

The lifecycle of E. multilocularis begins when the tapeworm’s microscopic eggs are excreted in an infected canid’s feces and dispersed into the environment, where they can live for up to a year.

When rodents (primarily voles and field mice) and rabbits ingest the eggs either through canid feces or from the environment, the eggs hatch into larvae that invade the animal’s liver and sometimes other organs, multiplying and causing severe cysts that grow like metastatic cancers.

When a wild canid or domestic dog then eats an infected animal, the larvae contained in the consumed animal’s cysts latch onto the canid’s intestines and grow into adult tapeworms that produce eggs, and the parasite’s lifecycle continues.

While the adult tapeworms aren’t typically problematic in wild canids, in domestic dogs the parasite can sometimes cause alveolar echinococcosis where, similar to what happens to rodents or rabbits, the tapeworm larvae invade the dog’s liver or other organs. Because domestic dogs are canids like their wild relatives, usually the adult tapeworms will live in their intestines without causing alveolar echinococcosis.

However, even if a dog doesn’t develop the disease, they will continue to excrete the parasite’s eggs in their feces — and those eggs can cause the potentially fatal disease in humans if they accidentally ingest the eggs.

“Dogs can act like the coyote or other infected canid, and then humans can act like the rodent if we ingest the (egg-infested) feces of dogs, coyotes, or foxes without meaning to,” says Dr. Harton.

Since a dog infected with the tapeworm may appear healthy, owners will not know the dog is shedding the parasite’s microscopic eggs in their feces. In fact, the dog confirmed to have been infected in Peterborough was not displaying any symptoms of having the tapeworm — it was brought to Sherbrooke Heights Animal Hospital for something unrelated.

However, when the hospital learned more about the pet’s lifestyle and its tendency to ingest rodents, they administered a specialized fecal test for enchinococcosis.

“The tricky thing with this tapeworm is that they don’t always show clinical signs, so it really a matter of doing the due diligence during our history taking and for owners to really keep an eye on their (dog’s) behaviours,” says Dr. Harton. “The risk factors for dogs truly is in eating rodents, and especially in an area where there are a lot of coyotes or foxes.”

While the most common way for humans to get alveolar enchinococcosis is by eating wild foods like berries and herbs that have been contaminated with wild canid feces, they can also get the disease if their dog gets wild canid feces in its fur, or from an infected dog’s own feces.

“For people, as long as they’re practising good, thorough handwashing after handling dog feces, fox feces, or coyote feces, their risk is really well-managed,” Dr. Harton says. “It’s the best technique — as well as washing your fruits and vegetables before consumption, even if you grow it in your own backyard.”

E. multilocularis is only found in the northern hemisphere, in parts of Europe, Asia, and North America. According to Public Health Ontario, E. multilocularis is now considered endemic in Ontario and was declared a disease of public health significance in 2018.

Infectious diseases surveillance reports show there have been four confirmed human cases of alveolar echinococcosis in Ontario since 2017, with the latest in 2022. However, the actual number of human cases may be higher, since people infected with the parasite can remain asymptomatic for five to 15 years.

Eventually, those infected will show symptoms of abdominal pain, weakness, and weight loss, as the tapeworm causes damage to the liver and other organs. If left untreated, the disease is invariably fatal.

While E. multilocularis had never been found in wildlife or domestic animals in Ontario prior to 2012, a study conducted from 2015 to 2017 showed that 23 per cent of postmortem fecal samples collected from 460 wild canids in southern Ontario — 416 coyotes and 44 foxes — tested positive for E. multilocularis.

Although none of the samples were collected from wild canids in the Peterborough area, Dr. Harton says there’s no reason to assume the situation is different in the region.

“We unfortunately just don’t even have information about the wild canids in Peterborough,” says Dr. Harton. “What we can do, though, is assume that our wild canids are just as infected as the other local areas around us where they did collect samples from, because wild canids don’t follow our public health (borders).”

Given that dogs infected with E. multilocularis often show no symptoms, Dr. Harton suggests the best action for dog owners to take is simply to be aware of the risk, maintain good hygiene for yourself and your pet, and know your dog’s behaviours and habits.

“I wish there was, but unfortunately there’s no quick and easy tell for this,” she says. “If your dog ingests rodents, then this should be a conversation to have with your veterinarian.”