GreenUP grew over 5,000 native plants in 2025 and supported the planting of hundreds of others. In celebration of these restoration efforts, along with newly installed tree identification signage at Ecology Park, GreenUP will highlight a few select native trees in a three-part series over the holidays.

Winter once drew a firm line through Ontario’s forests, having the final say on which species could endure and which could not. With the ongoing effects of climate change, that line is becoming less distinct.

When the cold begins to fade and spring arrives, some things may appear slightly out of place: pink blossoms on bare branches, unfamiliar leaf shapes emerging, or a species not expected to be seen this far north. These small changes don’t announce themselves as climate change, but together they hint at shifting boundaries and local forests responding to new conditions.

Southern Ontario is home to an area known as the Carolinian zone, a region that extends north from the Gulf Coast of the United States into Canada. While it makes up less than one per cent of Canada’s total landmass, the Carolinian zone supports more than half of the country’s native tree species. This extraordinary concentration of biodiversity exists at a climatic edge, where temperature has long determined which species could survive Canadian winters.

Among the tree species now appearing beyond their traditional ranges are eastern redbud, cucumber magnolia, and pawpaw — trees commonly associated with Ontario’s Carolinian forests. Each sits near the northern edge of their historical range, where winter cold once limited survival, flowering, or fruiting. These trees’ northward appearances reflect different paths to persistence, shaped by both environmental change and human influence.

With bright pink flowers emerging directly from bare branches, and large, heart-shaped leaves to follow, eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis) is hard to miss. Long valued for its ornamental appeal, this tree has been widely planted in parks, streetscapes, and gardens, often far beyond its historic range.

What has changed is not where redbud is planted, but instead, where it can persist. Increasingly milder winters have enabled this relatively short-lived species to survive and flower more consistently farther north, providing a clear example of how human activities and climate conditions intersect.

Listed as endangered on Ontario’s species at risk list, the cucumber magnolia (Magnolia acuminata) is Canada’s only native magnolia tree. Known for its wavy leaves, yellow-green flowers, and distinctive cucumber-like seed structure, this tree could once be found within mature forest landscapes.

Its limited distribution reflects both a natural narrow range and sensitivity to cold, particularly during early growth and flowering. As winters grow milder, the conditions that once limited survival at the northern edge of its range may be slowly easing.

Cold temperatures aren’t the only factor limiting this species. Although cucumber magnolia is the largest of North America’s native magnolias, capable of reaching more than 30 metres in height, its growth is slow and takes decades to mature. Young magnolias are especially vulnerable to late spring frosts, and even well-established trees are dependent on stable, mature forest conditions to persist.

Together, these traits make cucumber magnolia a species defined by patience. The future of this tree is dependent less on sudden change and more on long stretches of stability, where trees are given the time they need to grow and flourish.

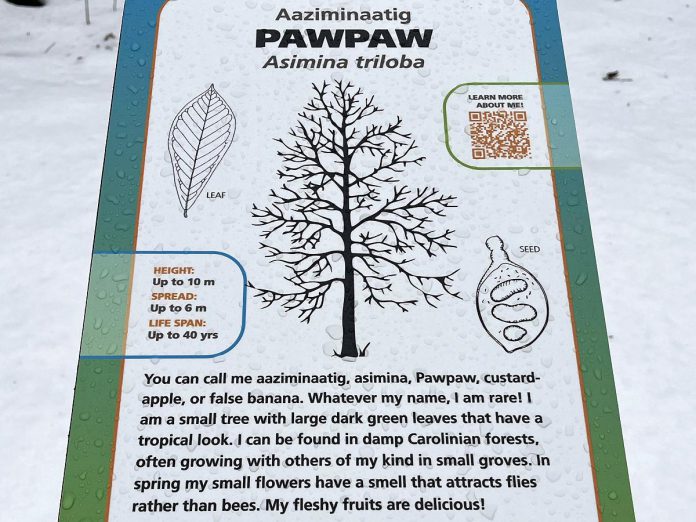

The pawpaw (Asmina triloba) offers a different kind of story.

This small understory tree produces green mango-shaped fruit with a soft custard-like flesh, which tastes more similar to banana or mango than anything else grown in Ontario. While not especially fast-growing in the area, the trees may take eight to 10 years to flower and fruit.

Historically, fruits from the pawpaw were eaten by large mammals that could carry and disperse the seeds across the forest. Today, pawpaw seeds are primarily dispersed over short distances by smaller mammals like raccoons, opossums, and foxes, while human planting has become an important factor in helping this species persist. Whether in yards, restoration projects or forest edges, people are now essential to pawpaw’s continued survival and spread.

All together, these trees show how Ontario’s forests are responding to changing conditions in their own respective ways.

Some, like redbud, show the immediate impact of human planting and milder winters. Others, like the cucumber magnolia, move slowly and depend on longer-term stability. And the pawpaw demonstrates how species that were once connected to the larger forest ecosystem now rely on people to help them thrive.

Observing these changes reminds us that forests are not static; they are living, shifting communities, shaped by both nature and human hands.

Visit Ecology Park to see these native tree species and the newly installed tree identification signage, funded in part by Trans Canada Trail, and featuring Anishnaabemowin translation of the tree names courtesy of Curve Lake First Nation and The Creators Garden.

You can support GreenUP’s work to restore native habitat locally by donating today at greenup.on.ca/donate-now/.