Prime Minister Justin Trudeau addressed Canadians on Thursday (April 9) about the best-case scenario of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada, which would see between one and two million Canadians infected by the novel coronavirus and between 11,000 to 22,000 deaths by the summer.

The modelling projections were released earlier on Thursday morning by the deputy minister of health for Canada Dr. Stephen Lucas, chief public health officer of Canada Dr. Theresa Tam, and deputy chief public health officer Dr. Howard Njoo.

And the best-case scenario for “success” is only for the first wave of the pandemic, and assumes the strongest control measures are in place to contain the spread of the virus.

“We’re at a fork in the road, between the best and the worst possible outcomes,” Trudeau said. “The best possible outcome is no easy path for any of us. The initial peak — the top of the curve — maybe in late spring, with the end of the first wave in the summer.”

“As Dr. Tam explained, there will likely be smaller outbreaks for a number of months after that,” Trudeau added. “This will be the new normal — until a vaccine is developed. But as we saw, that is so much better than we could face if we do not rise to the challenge of this generation.”

“The path we take is up to us. It depends on what each of us does right now. It will take months of continued, determined effort.”

Trudeau urged Canadians to keep practising physical distancing, staying home, and washing our hands to reduce the number of possible deaths.

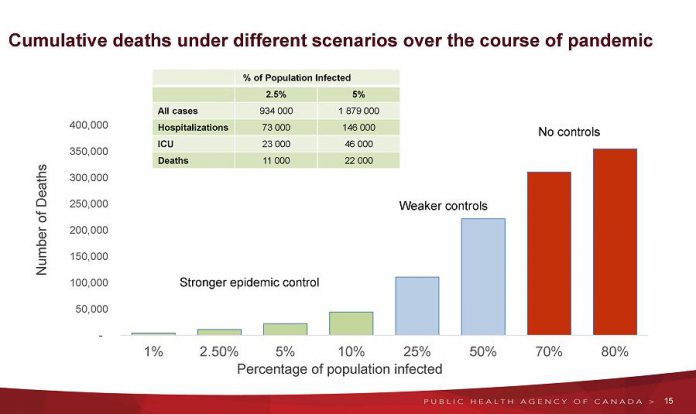

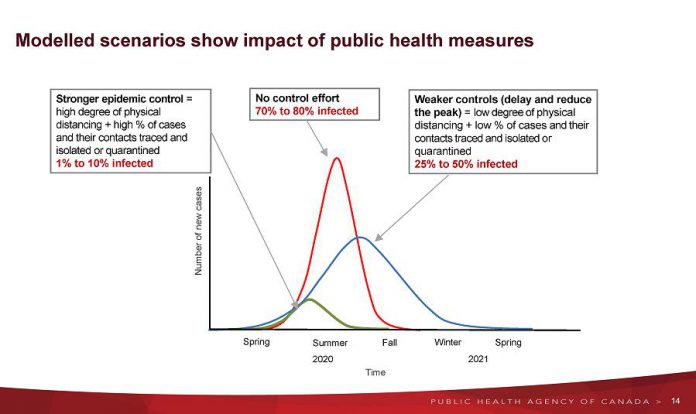

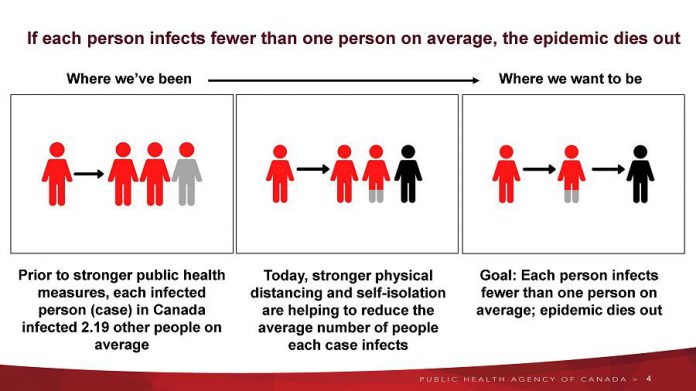

Earlier in the morning, public health officials had provided three scenarios — one with no controls, one with weaker controls (to delay and reduce the peak), and one with stronger controls — to estimate the range of the Canadian population infected and the potential duration of the pandemic.

According to these projections, strong control measures will result in between one and 10 per cent of the Canadian population being infected with the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

With 2.5 per cent of Canada’s population infected, there would be 934,000 cases of COVID-19, with 73,000 hospitalizations, 23,000 patients in intensive care units (ICUs), and 11,000 deaths. With five per cent of the population infected, cases would rise to 1,879,000, with 146,000 hospitalizations, 46,000 patients in ICUs, and 22,000 deaths.

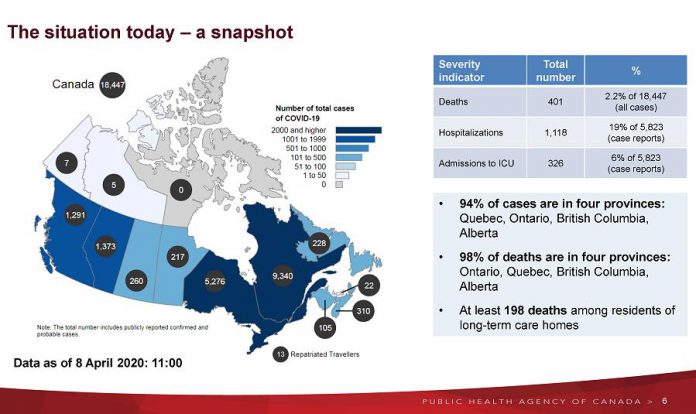

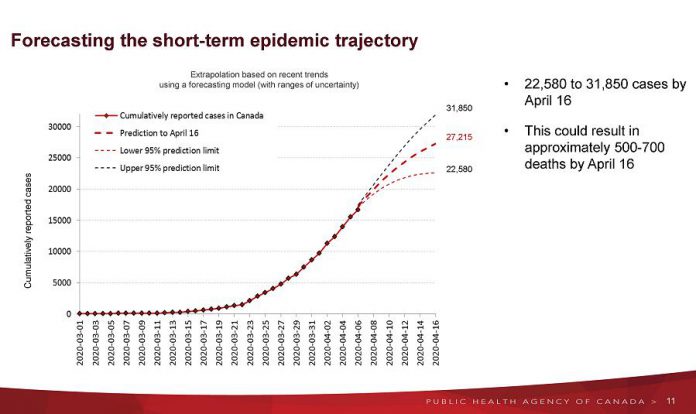

In the short term, public health officials are projecting 22,580 to 31,850 cases by next Thursday (April 16), with between 500 and 700 deaths.

Strong control measures include a high degree of physical distancing, along with a high percentage of Canadians with COVID-19 been traced (as well as their contacts) and isolated or quarantined. With strong control measures, the first wave of the pandemic would peak in early summer 2020.

Weaker controls — with a low degree of physical distancing and a low percentage of case and contact tracing and isolation — would result in 25 to 50 per cent of Canadians being infected, with the first wave of the pandemic peaking in fall. With weaker controls, as many as 200,000 Canadians would die from COVID-19.

With no controls, 70 to 80 per cent of the Canadian population would be infected, with the first wave of the peaking in late summer or early fall. With no controls, as many as 300,000 Canadians would lose their lives due to COVID-19.

Even under the best-case scenario, where the first wave of the pandemic peaks in early summer, continued public health measures will be required over time to manage future waves.

This include physical distancing, hand hygiene and respiratory etiquette, restrictions on international and domestic travel, case detection and isolation, and quarantine of contacts and incoming travellers.

Public health officials pointed out that Canada is at an earlier stage of the COVID-19 pandemic than some other countries, and has an opportunity now to control the spread of the virus and prepare the health system, which includes equipping hospitals to provide care for the more severe cases of COVID-19, increasing bed and clinic capacity for all COVID-19 patients, and expanding the health workforce.

The federal models contain inherent limitations. As simulations, they do not predict what will happen, but what might happen. They use both forecasting models (using data to estimate how many new cases might be expected in the coming week) and dynamic models (showing how the pandemic might unfold over the coming months).