As the manager of Harm Reduction Services with PARN – Your Community AIDS Resource Network in Peterborough, Pollock’s daily mission is to mitigate any harm associated with substance use.

As such, the annual day of substance use awareness and education, which will be marked from 1 to 4 p.m. on Wednesday, August 31st at Millennium Park in Peterborough, will see her train others in how to administer naloxone, a lifesaving medication that temporarily reverses the all-too-often deadly effects of overdose from opioid use.

Training people who don’t use substances to administer naloxone is key to saving lives according to Pollock, who was a member of the Mobile Support Overdose Resource Team (MSORT) prior to her current position.

“Even if a person who engages in substance use carries and is trained in administering naloxone, if they go down they can’t administer naloxone on themselves,” she says. “They rely on peers and others in the community who carry and have the training to administer naloxone. The more people who are trained, the better.”

So it that on August 31, Pollock and her colleagues will provide that training and also distribute naloxone kits, not only in Peterborough but also at similar events in the City of Kawartha Lakes, Haliburton, and Northumberland.

Prior to International Overdose Awareness Day, naloxone pop-up events are being held 1 to 4 p.m. on Wednesday (August 24) at Peterborough Square, 1 to 4 p.m. Thursday (August 25) at the Peterborough Public Library, and 1 to 4 p.m. Friday (August 26) at Victoria Park.

Training to administer nalaxone, notes Pollock, is “quite simple. It usually takes 5 to 10 minutes to complete. The training is pretty straightforward.”

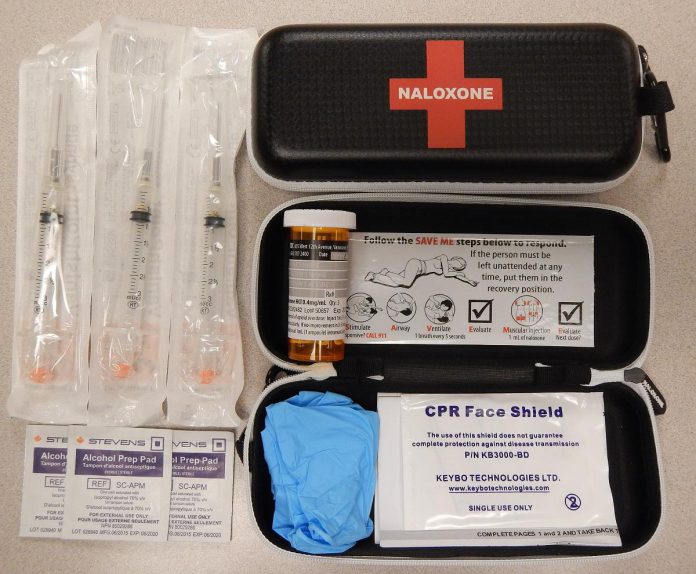

Pollock points out there are two types of naloxone: one administered nasally and the other injected intramuscularly.

“With both nasal and intramuscular naloxone, there are five steps,” Pollock says. “First, you ‘shake and shout’ to determine whether the person is responsive. If they are non-responsive, you call 9-1-1. When emergency services is on the way, you then can administer naloxone. If the person does not come around after two to three minutes after administering naloxone, you can administer another dose. You can continue to administer doses of naloxone every two to three minutes, until the person either becomes responsive or until emergency services arrive.”

“If the person does become responsive after administering one or multiples doses of naloxone, stay with them until emergency services arrive as naloxone can wear off and a person can fall back into an overdose,” Pollock continues. “Naloxone sends those with opioids in their system into immediate withdrawal — it is not fun. For this reason, it is important to administer naloxone only to someone who is non-responsive. If someone is on the nod from opioid use but is still responsive, naloxone is not necessary at that point in time. If someone does not have opioids in their system, naloxone will not harm them.”

She explains that intramuscular and nasal naloxone are the same medication, and both kits come with two four-milligram doses.

“The only difference is the method of delivery. The nasal naloxone is more widely requested as it is a more straightforward nasal spray, versus the intramuscular version which involves drawing up the medication into a syringe from a vial and injecting into a muscle.”

“Some have a preference for intramuscular for a few different reasons, one being familiarly with injection and another being the ability to titrate the dose, where that is not really an option with nasal naloxone,” says Pollock, explaining that drug titration is the process of adjusting the dose of a medication for the maximum benefit without adverse effects. “With the intramuscular, you can draw up a portion of the dose and see if that works. If it does, the fact that it’s a lesser dose will result in less severe withdrawal symptoms.”

Besides providing naloxone training and distributing naloxone kits, the Millennium Park event will also see various organizations — including Moms Stop The Harm, Peterborough Public Health, MSORT, Peterborough Safer Supply, and the Elizabeth Fry Society of Peterborough, as well as PARN — host information booths.

Through PARN, T-shirts will be available to purchase — with slogans such as ‘Get High, Not Die’ and ‘My Community Includes Those Who Use Drugs’ — to raise money for the organization’s Harm Reduction Program,

“The day’s real purpose is to provide the right answers to questions and correct any misinformation,” says Pollock, noting there’s no shortage of the latter. The more informed people are, the better — not only to reduce stigmatization but also to increase the number of people with naloxone kits at the ready. Pollock says the establishment of public naloxone stations, not unlike that of public defibrillator units, “would be a great thing to see.”

The advent of the Consumption and Treatment Services (CTS) location at Simcoe and Aylmer streets in downtown Peterborough, Pollock says, “was a long time coming,” adding it’s huge in terms of “keeping people alive.”

“One of the big impacts of overdose is people using alone,” she explains. “The CTS addresses that. People can go to that site, they can use, and they can have after-care to make sure that, if they go down, there’s a paramedic, a nurse practitioner, and harm reduction specialists to take care of them.”

While Pollock recognizes some people have concerns with providing resources for substance users, she points out the alternative can be worse.

“People may say we’re enabling addiction because we distribute injection and inhalation equipment, but it’s a less of a cost for taxpayers than to cover the cost if users become infected with HIV or hepatitis C or other harms attributed to the reusing and sharing of drug using equipment. And if there are fewer calls for overdoses, that means somebody who goes down when they’re shovelling snow will more likely get quicker attention.”

Pollock also counters the misconception that making resources available for substance users somehow encourages drug use.

“Nobody’s going to walk past a needle exchange, a CTS, or a safe supply pilot project and say ‘Oh, opioids! That’s an idea.’,” she says. “That just doesn’t happen. We know that substance use is a fact of life. We’re just trying to mitigate the harm around that.”

That harm includes the dangerous quality of the drug supply — a situation that showed itself in a big way during the pandemic and continues.

“The supply gets cut (with other substances) in part because access to cross the border became more limited or simply because it’s cheaper and more accessible to cut it with other substances,” notes Pollock, adding “So they just cut and re-cut and re-cut — that’s a huge thing we’re seeing right now.”

“We’re trying to move away from the language of overdose toward the language of drug poisoning. Overdose, in a way, feels like it’s putting the onus on the substance user — it’s on them because they’re using too much. But that’s not what’s happening. What’s happening is they’re not getting what they’re buying. They’re buying opiates or they’re buying cocaine, but it has benzodiazepines or fentanyl in it. That’s a large part of why people are going down.”

Despite all the stresses and stigma-induced frustrations, Pollock still loves what she does and is inspired by those she serves.

“I love the substance-using community so much. They’re such beautiful people. They give me hope. It’s not them that have to change — it’s us that have to change! It’s our support of and for them that needs to change.”

“The substance user, in my experience, is more likely to give you their last dollar or their last cigarette than the next person,” Pollock reflects. “I see so much heart and compassion and generosity from the substance-using community. It hurts a lot when I hear stigmatizing language directed at them.”

At the end of the day, Pollock says she and her team members aren’t there to encourage or discourage substance use, but to support substance users whatever their goals may be, whether moderating their use, abstaining from use, or just using more safely.

“Harm reduction doesn’t impose goals upon them,” she says. “We better enable those who do use substances, to do so more safely.”

The original version of this story has been revised to clarify the steps involved in administering naloxone and updated with other corrections.