Hamilton-based musician, artist, and author Tom Wilson believed he was of Irish heritage for the first 54 years of his life — and then he discovered he was actually Mohawk.

Students at Immaculate Conception Catholic Elementary School in Peterborough were entranced by Wilson’s story, which he shared with them during an event at the school on Thursday afternoon (December 8).

Wilson, who was in Peterborough to perform with his band Blackie and the Rodeo Kings at the Market Hall, is an artist ambassador for the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund in partnership with Sony Music Publishing. The Downie & Wenjack Fund’s artist ambassador program brings Indigenous and non-Indigenous musicians, artists, and knowledge keepers into legacy schools to inspire student leadership and forward the journey of reconciliation in communities.

F=

In addition to making a donation to the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund as part of Sony’s “Season of Giving,” Sony bought Wilson to Immaculate Conception school to speak with 50 young students about his experience and about reconciliation.

Also speaking at the event were Lisa Prinn, manager of education and activation from the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund, and Rebecca Watts from the Lovesick Lake Native Women’s Association, along with representatives from Sony Music Canada.

“I’m 63 years old, so I’m probably the same age as most of your grandparents,” Wilson told the group of young students. “But only nine years ago, I found out from a complete stranger that I was adopted. Now that’s a long life to live in mystery and not knowing your origins, and always suspecting that your mom and dad aren’t your mom and dad. That’s the life I lived for 54 years.”

Wilson recounted how, two weeks after he found out he was adopted, he was driving his cousin Janie home after celebrating the birthday of one of Wilson’s grandsons. Janie, who is 18 years older than Wilson, has been around Wilson for his entire life and is the matriarch at family gatherings. When Wilson told Janie he had found out he was adopted, she revealed a secret that would change his life.

“My cousin Janie turned to me and said ‘Tom, I don’t know how to tell you this. I’m sorry and I hope you forgive me, but I’m your mother’,” Wilson told the students, adding that both she and his birth father were Mohawk from Kahnawake First Nation, located outside of Montreal.

“I grew up for 54 years thinking I was a big, puffy, sweaty Irish guy — I’m actually Mohawk from Kahnawake,” Wilson said. The couple that raised Wilson, Bunny and George, were actually his great aunt and uncle and “were completely loving.”

“Since I found out that I’m actually Indigenous and not Irish, it’s now my goal through my art to work every day to put the Mohawk culture into a bright light and to work for Indigenous issues, Indigenous problems, to go and try to fight for communities. It’s what I’m doing here today with you guys.”

Wilson — whose Mohawk name is Tehoh’ahake, which means “Two Roads” — also told the students about a project he’s spearheading to replace trees that were destroyed during the so-called “Oka Crisis” in 1990, when Mohawk warriors in the community of Kanesatake took a stand against the Quebec police, the RCMP, and the Canadian Army to prevent ancestral land from being developed. Related protests also took place in Kahnawake First Nation.

“My active role is not just through the visual art that I create, and it’s not through the music that I write, and it’s not through the book that I’m writing right now — it’s by taking an active role,” Wilson said.

“Hopefully all of you feel inspired by what you’re learning through the Downie Wenjack people and hopefully will be able to stand up and take an active role in making this a better country, a better planet, a better community for all people to live in,” Wilson said.

“I don’t want to put it on you guys, but it’s actually your job, because my generation has failed miserably at trying to do this — but we’re working hard to try to make it better.”

Along with his art and his tree-planting project, Wilson told the students he has started the first Indigenous scholarship at Hamilton’s McMaster University for any Indigenous students in Ontario.

He also shared the story of his arrest for supporting “land defenders” from the Six Nations of the Grand River in Caledonia, before reading a passage from his best-selling memoir Beautiful Scars and performing an a capella version of his song “Grand River” from the latest Blackie and the Rodeo Kings record O Glory.

Wilson also answered a number of questions from the students about his music and his art, and was presented with a thank-you gift made by the students.

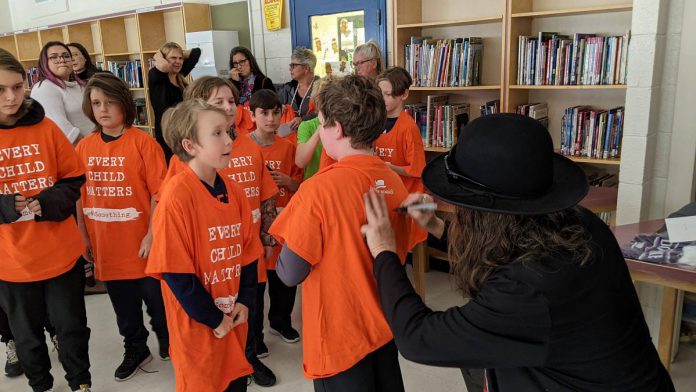

He then helped hand out “Every Child Matters” orange t-shirts to the students and autographed them.