Does an experience define you, or do you define the experience? In the case of the inspiringly adaptable Cheryl Strayed, it’s one then the other.

But behind the Oprah-approved unlikely self-help guru lies a self-aware firebrand with a litany of battle scars and a virtuosic sense of pace towards a suspenseful splintered narrative.

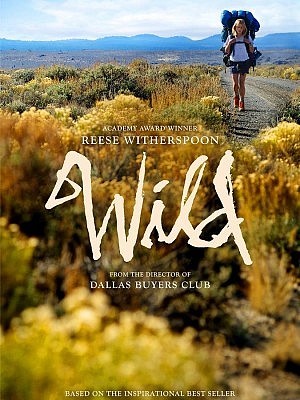

Strayed’s deservedly lauded memoir Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail is the subject of acclaimed Canadian filmmaker Jean-Marc Vallée’s new film Wild, adapted to the screen by Nick Hornby (High Fidelity, About a Boy). I saw a screening of the film, which opens in select theatres in Canada on December 5th, at the Toronto Film Festival in September.

At age 22, Strayed (Reese Witherspoon) suffers the devastating death of her beloved mother Bobbi Lambrecht (Laura Dern, luminous). Having effectively lost the love of her life, Strayed descends into a nihilistic lion’s den of casual sex and heroin abuse. Strayed describes this period as her “genesis story.” Her marriage also crumbles due to the strains of her self-destructive behaviour.

Determined to get back to the woman her mother thought she was, Strayed sets out on the frighteningly ambitious undertaking of hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, more than 1000 kilometres of rough path carved along the coast of northern Mexico to southern British Columbia. Upon signing her divorce papers and selecting the surname “Strayed” as a sort of “Red A” sown to her bodice, Strayed begins the crawl back to herself.

The seemingly insurmountable reality of what an undertaking like this would actually consist of is never ignored and long shots are frequently spent on the more mundane elements of Strayed’s struggle. A solid five minutes are used voyeuristically hanging onto Witherspoon’s small frame battling to get a 65-pound bag on her back.

It’s amusing and a recurring source of comic relief. There is much laughing and screaming in the face of frustrating tasks.

This reality also lingers on the nature of the lone female in the middle of nowhere. Brief interactions with fellow kindred explorers and hunters have varied results. The threat of sexual violence always is palpable, even if like the text it is used as a nail-biting red herring.

Comparisons to Into the Wild are inevitable yet trite. Both are breathless non-fiction character studies of solitary environmental immersion, but Strayed’s odyssey comes from a considerably more genuine angle: having lost she wants to earn back. The trail becomes a purifying walkabout rather than a self-indulgent, muscular proving ground.

Vallée has always been an actor’s director, eliciting uncharacteristically complex performances from actors not generally regarded as being particularly versatile thespians. Witherspoon’s dynamic and bruised portrayal of Strayed has been praised for its Hydra-like emotional volatility and not for its lack of makeup. But Witherspoon has been turning in great work for years. From her smart interpretation of the promiscuous valley girl-turned-bookworm in Pleasantville to her cringe-inducing personification as everything-that’s-wrong-with-western-society in Election, Witherspoon imbues often underwritten roles with her memorable, sly intelligence. I’ll be placing my Award bets on her this season.

As with C.R.A.Z.Y. and Dallas Buyers Club before it, Vallée continues to sympathetically probe the eventually not-so-strange nature of social outsiders. This is partially achieved by bestowing them with symbolic animal totems that act as familiar spirits. In Wild, Strayed occasionally encounters a fox that subtly informs her that the literal and figurative path she is walking is the right one.

Strayed may have a dedicated following of young women but, trust me, this story knows no gender boundaries. I wept like a destitute hyena during my screening. Few depictions of drug use or casual sex can actually encapsulate the head-spinning highs and confusing carnal logic actually associated with them. The pathos is certainly there; but, more importantly, so is the practical acidic experience.

When I spoke with Strayed after the film, I thanked her for sharing her story and explained how I could sympathize with some of the darker aspects. She took my hand in hers and said serenely “I’m sorry.”

For that is life and that is what this story is about — getting back to life.