November is Radon Gas Awareness Month in Canada.

Huh?

You’d be forgiven if you didn’t know that. For that matter, you’d be forgiven for not knowing what radon gas is. But that’s all changing as The Lung Association, Health Canada, public health units, and even some municipalities are stepping up efforts to inform Canadians about radon gas, and why it matters.

It matters, because it can kill. It’s the second-leading cause of lung cancer in Canada behind smoking. What’s more, you can be exposed to it in your own home.

First, a quick primer. According to Steven W. Mahoney of the Radiation Safety Institute of Canada, radon is a naturally occurring by-product of uranium as it breaks down, and can be found in higher concentrations depending upon where you live in Canada. But make no mistake. It’s everywhere.

Including here. In the Kawarthas. Should you be worried?

Rob Reymen, the acting Chief Building Inspector for the City of Guelph, notes that Health Canada did random samplings of homes for a nationwide snapshot of radon gas levels over a two-year period ending in 2012. When five of the six postal codes in Guelph came back with high levels, Guelph decided to be proactive.

“We wanted to make sure we got it right,” Rob tells me. After “exhaustive” consultations with health units and other stakeholders, the new bylaw went into effect September 1st.

“That’s for all construction, not just residential homes,” he says from his office in the Royal City. “It’s for ICI, office buildings, schools and things like that. [Contractors] will have to take into account radon mitigation in their designs and construction.”

Would that ever happen in the Kawartha region? Not likely, at least in the near future. Wanda Tonus, a local public health inspector, says the Peterborough County-City Health Unit is not pushing for the kind of response Guelph has implemented.

Dean Findlay, Peterborough’s chief building official and Manager of the Building Services Division for the City, has not seen anything in his 11 years on the job that would prompt him to suspect a problem here.

“I wouldn’t be recommending a specific municipal approach unless we had some inkling that there was an issue,” he says.

Findlay notes there are already provisions in the Ontario building code for areas identified as “hot spots.”

Well yes, counters Reymen in Guelph: there is language in the building code, but it’s a bit on the vanilla side: “‘If you believe that radon is a problem in your area…’ — it’s kind of grey, right? It leaves it up to us as building officials,” to make the call.

Radon gas is covered in the federal building code for public lands, for example — but those provisions are not binding to provinces or municipalities. Still, there are places in the country opting to be proactive. Reymen says BC has adopted the federal standard. Mahoney writes that Quebec has tested all of its schools, and Saskatchewan has gone one step further by testing all public buildings as well.

Generally, the area of concern for homeowners is the lower-most living space — for most, that’s a basement rec room. But then, what if you live in a basement apartment?

The takeaway message here is to have your living space tested. That’s done with a radon testing kit that you can source free from a limited supply offered by the Peterborough Health Unit (not all health units do), otherwise you can buy one. Merrett Home Hardware Building Center and Home Depot both sell them locally for under $20. That kit goes to the lowest-most active living space and stays there for three months. Then you send it away and the results come back in a couple of weeks.

According to Wanda at the Peterborough Health Unit, the magic number is 200 becquerels per cubic metre (200 Bq/m³) or lower. If it’s higher, you need to call a certified contractor. Most health units maintain a listing of contractors qualified in the task of radon gas mitigation.

Bud Ivey, a public health inspector with the Haliburton, Kawartha, Pineridge District Health Unit in Brighton, says it’s also a good idea to test for radon before, and after a planned renovation — or in concert with restoration following a fire.

He agrees that for most, the radon gas story flies under the radar.

“Even for public health, it’s fairly new. Yes, it’s been ‘out there’ but it hasn’t been as prevalent,” he says. “Only now it has come to light that the research has shown that there’s lot more deaths attributed to radon gas than previously thought.”

Which brings us back to National Radon Gas Awareness month, timed when most Canadians close up the house for the winter and start to cocoon. No need to panic, but now’s the time to test your living space.

Given the risk, it’s important to be vigilant. Radon gas is a silent killer that’s been silent for far too long.

Mike Holmes on Radon

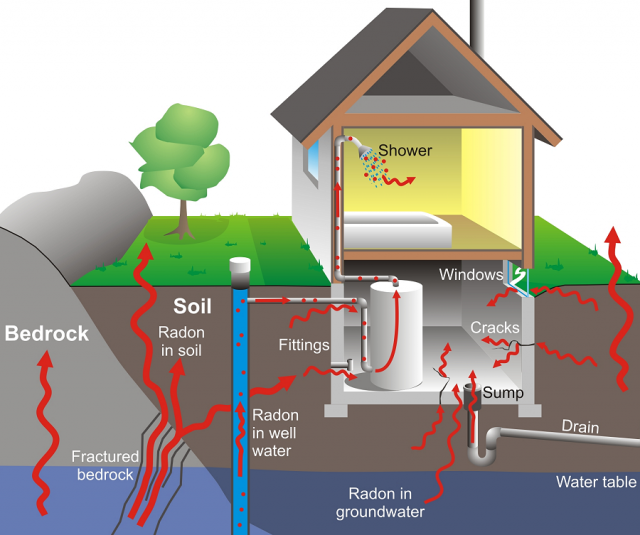

Images courtesy of The Lung Association.