After noticing a lack of Indigenous language and culture curriculum in Ontario public schools, Ashley Wynne — an Anishinaabe mother of four — is channelling her frustrations into meaningful action by opening an Indigenous culture-based private school.

The school, called ‘Sage and Sunshine’, is located at 1434 Chemong Road in Nogojiwanong-Peterborough and will open in September for children aged four to nine.

Wynne is an early childhood educator with over 10 years of experience working with children. She homeschooled three of her four children throughout the pandemic, incorporating Indigenous language and culture into the Ontario curriculum. The idea for Sage and Sunshine grew from there.

“I had planned on homeschooling my kids forever after the pandemic is over, because this kind of learning is what I want for them,” Wynne tells kawarthaNOW. “Then the Nogojiwanong Friendship Centre saw the activities I was doing with my kids because I was posting them online. They sent me some families who were struggling with online learning.”

After a year of success schooling Indigenous children in a way that connects them to their Indigenous heritage, Wynne looked into opening a private school. She recognized that many other Indigenous families living off-reserve are also looking to educate their children in a way that values their roots and traditional knowledge.

When Sarah Susnar, co-owner of Lavender and Play in Peterborough, told Wynne she had a vacant classroom for the school, Wynne committed fully to the project this past January.

Although the experience of homeschooling during COVID-19 pushed Wynne to bring Sage and Sunshine to life, the project is a long time coming. Wynne is passionate about bringing Indigenous language and culture to urban Indigenous children and has advocated for years to get more Indigenous teachings into public schools.

“When my first child started public school, I called the school board and asked if I could get her into one of the schools that teach Ojibwe,” recalls Wynne. “They said that they couldn’t take anybody that’s not in the right district.”

Wynne continued to feel disappointed with her children’s access to Indigenous education when the once-a-week, hour-long, after-school Ojibwe class her oldest child attended shut down after the teacher left and was not replaced.

Wynne has continued to fight for her three younger children to have access to their culture in school.

When the pandemic hit, Wynne proved she could take her children’s cultural education into her own hands — an education she feels is vital for urban Indigenous children to have to keep their Indigenous culture alive for future generations.

“It’s a lost language and a lost culture because of what happened in residential schools,” notes Wynne. “We just have lost all our culture. This is the generation that’s getting it back and starting to learn more about what happened. We need to get it back so it can go on for more generations, or it will just die here.”

Wynne grew up in Sault Ste Marie as an urban Indigenous child whose only access to her culture was the Ojibwe language. Wynne’s non-Indigenous mother had no knowledge to pass on and, according to Wynne, neither did her Indigenous father, who had been displaced from his culture.

“My dad doesn’t know anything about his culture,” says Wynne. “He wasn’t allowed to practice his culture. Growing up, I didn’t think anything of it. I didn’t realize that I was missing out on so much.”

Wynne notes she did not even hear about the residential school system until she was in college at age 23.

“That was my awakening,” Wynne recalls. “Then I knew to dig deeper. Over the years, I’ve done a lot of work.”

Wynne is proud of having done that work to pass her Indigenous culture along to future generations, to ensure the children at Sage and Sunshine do not experience the same disconnect to their heritage as she did.

She says the children at Sage and Sunshine will be proud of their culture, and the incorporation of Indigenous teachings in their school day will feel natural to them — the same experience Wynne’s own children have had from her homeschooling.

“They’re just immersed in it, so they’re proud of who they are,” says Wynne. “They’re aware of everything that happened — that’s something I didn’t learn until college. I’m proud of them for that.”

A typical day at Sage and Sunshine will incorporate Indigenous language and culture and have a flexible schedule to allow children to have as much time as they need for each task. Elders and other knowledge keepers will also visit the school to teach lessons.

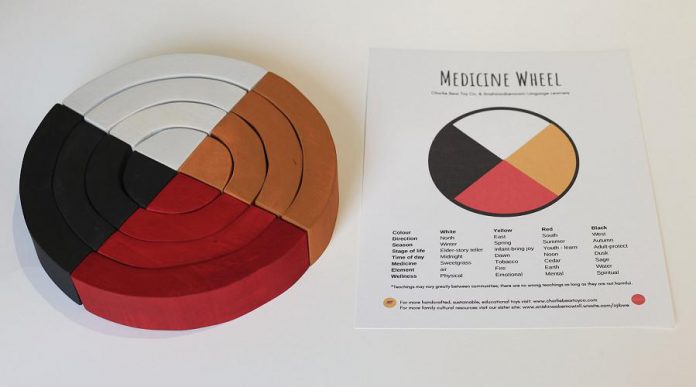

“Elders are the most highly respected people in our community,” says Wynne. “Each age group has specific roles and responsibilities which can be indicated on the medicine wheel. The youth (red) learn. Elders (white) share wisdom. Therefore, elders and youth are especially connected.”

In a combined classroom of kids aged four to nine, children can learn at their own pace. Wynne notes that, in this combined learning environment, the older children gain pride from helping the younger children.

“Traditionally, that’s how Indigenous people thrived from learning,” says Wynne. “We would learn in families and communities.”

Although Wynne has fought to keep the cost of Sage and Sunshine tuition low, many of the Indigenous community are in a lower income bracket, so she is raising funds to support eight Indigenous families to attend the school.

“Many Indigenous families are unable to pay private school tuition fees, and I don’t want this to be a barrier for them or an added stress on their families,” explains Wynne. “Money should not be the determining factor for whether or not their children can have access to their culture every day at school.”

For those looking for an Indigenous-led organization to support in response to the uncovering of unmarked graves at Canada’s former residential schools, Wynne says her GoFundMe campaign is a great place to start.

Wynne notes schools like hers begin to redress the injustices exhibited in the Canadian residential school system.

“School is the way they took our culture, so I think it is the way that we should be getting it back,” Wynne points out.

While learning about their culture is beneficial to the Indigenous children at her school, Wynne adds that Indigenous teachings can also offer a lot for the future of Canada as well. For example, Indigenous perspectives could be vital in years ahead as we continue to tackle the climate crisis — such as the Indigenous teaching called the seven generation philosophy.

“It’s acknowledging the seven generations before where you are now got you to where you are now,” Wynne explains. “Every decision you make, you need to think of the even generations forward. That’s a big reason that I’m starting the school — for the seven generations to come after me.”

To donate to the Sage and Sunshine’s GoFundMe and help eight Indigenous children attend the school, visit gofundme.com/f/tuition-help-for-indigenous-children-in-ptbo-on.

If you are not able to donate but would still like to support the school, Wynne asks that you spread the word.

“Please tell everybody you know,” Wynne urges, adding she would also welcome suggestions on any other programs or funding opportunities to help support Sage and Sunshine. “I really appreciate all the resources that have been shared with me.”

To learn more about Sage and Sunshine, visit their website at sageandsunshineschool.com. You can also follow the school on Facebook and Instagram.