“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell just as sweet.” So says Juliet in Shakespeare’s tragic romance Romeo and Juliet. Juliet is bemoaning the fact that a name may carry negative or positive connotations that are separate from the qualities and characteristics of the subject itself.

What is plastic, if not just a name we give to some polymers and not others? The word polymer means “of many parts.” One of the most common natural polymers is cellulose, which is biodegradable and found in the cell walls of plants.

Synthetic polymers, or plastics, are most often made from the abundant carbon atoms available in fossil fuels. Fossil fuel extraction has enormous negative impacts on the environment, including habitat destruction, the use and contamination of freshwater, and infringement upon the lands and rights of First Nations peoples.

I’d like you to step back and consider the name “plastic” in this tragically wasteful romance. What do we actually mean when we say something like, “plastic is bad and we should stop using it”?

I am not here to defend plastic or waste. I am here to say that figuring out how to live more sustainably is not just about absolutes. We must think about the nuances of a problem or we may end up blindly accepting solutions that only cause more problems without even recognizing the underlying problem.

Let’s create some space to think about the complexity of our romance with plastics and the waste management strategies necessary to keep ourselves and the planet healthy.

How did this problem of commercial plastic begin?

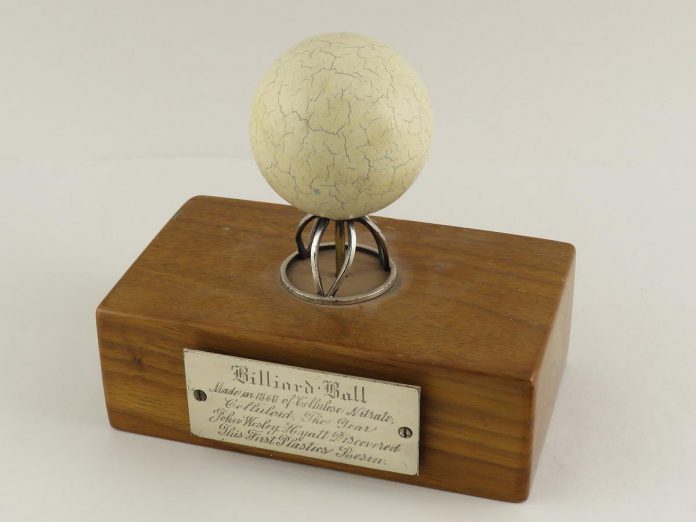

In 1869, John Westley Hyatt — an inventor living in the United States — discovered that cellulose and camphor could produce a pliable material which he called celluloid. Hyatt was prompted to create this malleable material by manufacturers of billiard balls, who were desperately looking for a substitute for ivory. The invention of plastic helped to reduce, in part, the demand for ivory that drove the hunting of endangered elephants.

This is not the only application of plastic that had some environmental value.

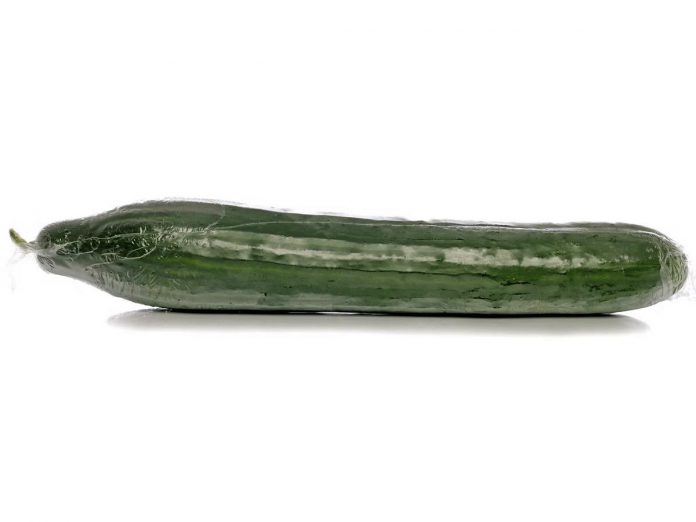

Let’s take a more familiar example: shrink-wrapped cucumbers. That thin film of plastic is designed to double the refrigerated shelf life of that cucumber from one week to two weeks. By using plastic packaging, the producer of that cucumber made an effort to prevent food waste.

Food waste is a big problem that contributes to climate change. When organic materials decompose in the landfill, they release a surprising amount of methane. Methane is one of the most potent greenhouse gases, trapping heat in the atmosphere 25 times more effectively than carbon dioxide.

Shrink-wrapping cucumbers seems like an attempt to balance the carbon emissions and waste from that plastic with the emissions produced by food waste.

There are biodegradable plastic packaging options in development that may be able to solve the waste problem created by shrink-wrapping food. We can also reduce methane emissions by composting instead of landfilling organic waste.

But the underlying problems remain: how we source and distribute food, and how we plan our meals so that we reduce food waste.

Even with that shrink wrap and other methods of extending shelf-life, a whopping 47 per cent of wasted food comes from households. With the rising cost of food these days, that amount of waste is a big problem for personal budgeting and for creating methane emissions in our landfills.

Plastic will continue to be the material of choice for manufacturers the world over. Unlike good ol’ glass, plastic is often very lightweight. The cost of production for most types of commercial plastics is similar to the costs for glass; however, glass is heavier and therefore requires more fossil fuels to transport.

For this reason, it can be hard to convince corporations to bottle things like beverages in anything other than plastic and harder still when the environmental benefit is offset by a marked increase in the use of fossil fuels for transportation.

Here’s another plastics puzzle. Which option is more sustainable: food storage containers made from stainless steel that was mined and manufactured in China and then shipped overseas, or from recycled plastic reformatted in North America and transported by truck to your local shop?

If we look at the whole life cycle of these materials, it’s difficult to identify a definitive winner. The environmental impact associated with mining the raw material used to make stainless steel is huge. Then consider more carbon emissions from shipping from China to Canada by air or sea.

By comparison, the materials used to manufacture recycled plastics are available locally, and that reduces the impacts of shipping to the recycling facility and to market.

But plastic recycling is an energy-intensive process, and plastics in general are less effectively and frequently recycled when compared to steel. Also, unlike those nearly indestructible stainless-steel containers, plastics do age and break.

While the stainless steel may have a slight edge over recycled plastic, either way we are dealing with underlying problems that still need solutions.

One underlying problem is the need to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels. Another underlying problem is that too many products are designed without consideration for a circular economy.

What does “circular economy” mean? In a circular economy, products are designed for change and sustainability. Products are made with as much re-used materials as possible and as few raw resources as possible. Products are intentionally designed so they can be repaired, re-used, and re-purposed into new products long before they need to be recycled or sent to the landfill.

Our entire romance with everything “plastic” doesn’t have to be tragic. We need to appreciate and tease out the nuances. In those nuances we can find the underlying problems and the solutions that avert environmental tragedies.

Long-term solutions need to move beyond banning single-use plastics. We need legislation and funding that empower the circular economy.