Imagine shopping at the grocery store, knowing full well there’s a very good chance that at least one of the items in your cart will make you sick. Still, you have to eat, so you take a chance and hope for the best.

Fortunately, we can rest easy that the food we buy undergoes rigorous and regular testing. If a problem is detected or even suspected, that information is shared widely with a product recall issued almost immediately.

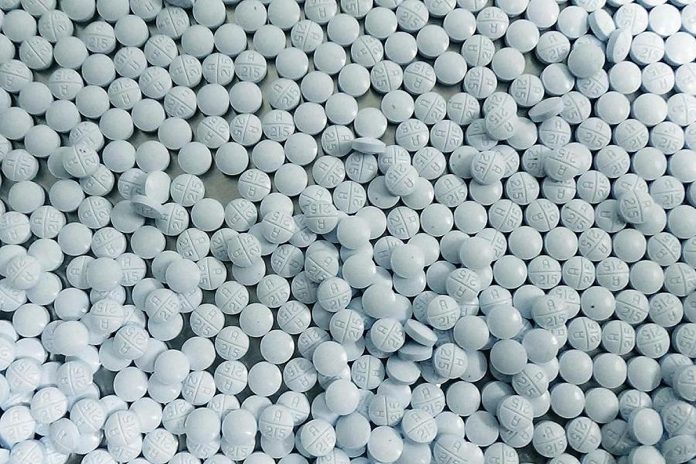

Across the country, and most certainly here in Peterborough, people who use illegal drugs don’t have such safeguards. When buying and using opioids, it’s a frightening game of Russian roulette.

As of the end of July this year, 31 people in Peterborough had died from using toxic illegal drugs. Another 234 received lifesaving attention from paramedics. At Peterborough Regional Health Centre during the same period, 343 emergency department visits were preceded by the use of tainted drugs.

Nancy Henderson and Carolyn King are certainly well aware of these numbers, and those recorded locally in preceding years. But rather than simply hope things will get better on their own — which won’t happen — they are wholly dedicated to the local success of a safer supply initiative funded through Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addiction Program (SUAP).

The Peterborough 360 Degree Nurse Practitioner-Led Clinic is the lead organization affiliated with the project, with initial research support provided by the Trent/Fleming School of Nursing. The project enables assessed participants who use drugs to access regulated substances from a legal source.

According to Henderson, the program’s evaluation manager, what was originally envisioned as a 10-person pilot program in May 2021 is now funded to take on a total of 50 people. That’s the result of “a very big ask” in the form of an amendment that was requested in June 2021 and was subsequently approved in December of that same year.

“We were proposing a 10-person pilot program and that just didn’t make sense to me,” says Henderson, noting the deaths of 44 people from poisoned drugs in 2021 provided all the motivation she needed to apply for funding to take on more participants.

“I was out in the community doing research to understand the enablers and barriers to treatment and to safer supply. I saw the need for this program. I worked in safer supply programs in Ottawa and Toronto, so I knew the potential of these programs. I’ve seen them work really well — I wanted that for Peterborough.”

King, the safer supply program supervisor, came on board in late February of this year, initially as supervisor lead of the now nine-member program administration team. She brought to the effort her prior harm reduction experience working with PARN, which was “experiencing the brunt of the overdose catastrophe” locally.

“When I saw the opportunity to be part of a specialized, really progressive forward-thinking project, I had to be involved,” she says.

In a province where, in 2021 according to the Office of the Chief Coroner, unregulated fentanyl was a factor in 86 per cent of all opioid-related deaths, the program prescribes safe pharmaceutical opioids to those who qualify following an extensive assessment conducted by physicians and nurse practitioners. At this point, the Peterborough program has 25 participants — halfway to its funded target of 50 participants by spring 2023.

But, notes Henderson, the program isn’t simply about ensuring safe supply for those enrolled, as potentially life saving as that is.

“It’s not just a prescription,” she says, adding “It’s full primary care, it’s full social services support, and it’s support from people with lived experience.”

“We’re here to support people making change in their lives as they choose. The goal doesn’t have to be abstinence. The goal can be whatever they want it to be. We’re here to facilitate that. It’s not just saving people lives. It’s an opportunity for people to make changes if they want to.”

“When you take the focus off worrying about being dope sick, there’s an opportunity to do other things. There’s an opportunity to look into health issues that you’ve been ignoring for a long time. There’s an opportunity to look into getting your ID figured out and getting housing sorted out.”

King explains that, when program applicants come off the waiting list, they first meet with a nurse practitioner who acquires their full health history and determines their primary health and social support needs before they receive a starting prescription.

Over the following weeks, program participants meet with their prescriber to adjust their dose “up to the point where optimal outcomes can be achieved.”

“Once the prescription stabilization has been achieved, that’s when the other primary care and social support needs can start to be addressed,” notes King.

“We look to build relationships based on a trust that encourages people to engage with us in a way that they might not with other mainstream medical programs where they might have experienced stigma or harmful attitudes or, in too many cases, denial of treatment.”

“We aim to be kind of a one-stop shop where people know they can trust us and feel safe coming in, giving us the full story of what they’re wanting to work on in their lives or what is working well. Our job is to support that.”

The program, says Henderson, “started by talking to people who use drugs,” noting it was mapped out “based on what they were asking for.” Next came the formation of an advisory committee comprised of people with “lived experience.”

“People who use drugs need to be involved and need to lead the way with these programs or they’re not going to work,” Henderson adds. “People who use drugs know how to keep themselves safe. They’ve been doing that for years. We need to listen and keep improving.”

Another key ingredient, says King, has been forging and maintaining relationships with service providers such as MSORT (Mobile Support Overdose Response Team), FourCAST, Consumption and Treatment Services, local shelters, and partner pharmacies.

If you guessed Henderson isn’t satisfied with the program’s 50-participant limit imposed by its funding, you guess right. She’s anxiously waiting the next call-out from Health Canada to put in another application to secure funding for a program extension.

Meanwhile, for both Henderson and King, the work they’re doing demands a 24-7 commitment. That’s something that they’re both more than OK with.

“My life is about harm reduction,” says King. “It doesn’t stop when I clock out. I try not to talk or think too much about my paid work, but I’m always ready to have a conversation with somebody or seize on education opportunities.”

“When I go to appointments or to the grocery store and somebody finds out what I do and wants to hear about it, I take those opportunities to spread the message that harm reduction saves lives.”

At the end of the day, notes Henderson, program success is rooted in participants being “able to make changes in their lives” combined with “people coming and wanting to get into the program … people who don’t go to any other services. That shows the program is working; that people trust it.”

Safer supply, says King, “is sort of a new frontier. It’s not a new concept but it’s new in its execution across Canada. Getting the team here up to speed on a very niche area of primary care, a very niche area of harm reduction, is a huge task — a very steep learning curve.”

“We are given a tight timeline and failure is not an option. We need to take what we’ve been given and say thank you and then ask for more.”