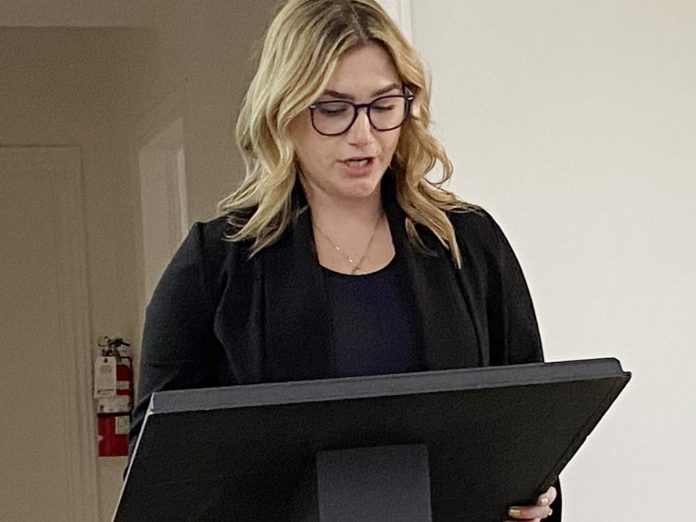

Publicly reliving a horrific day that “will be seared into my mind for the rest of my life,” Haley Scriver stood at a speaker’s podium on Tuesday morning (December 19) to formally announce a fundraising initiative aimed at raising money for mental health services and supports.

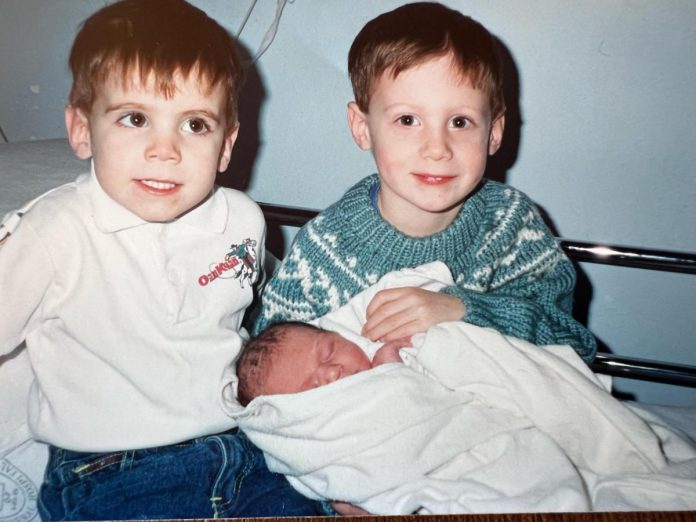

Roter’s Reach Mental Health Awareness is a not-for-profit venture founded in memory of Eric Roter, 32, who, on September 25, 2023, took his own life — 13 years after he was first diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Scriver, who is Eric’s sister, was supported at the announcement by her brother Sam, her parents William and Joanne Roter, and several extended family members and friends.

While the purpose of the gathering, held at Century 21 United on George Street South in Peterborough, was to launch the campaign — more information is available at rotersreach.ca where donations can also be made — it also served as a platform for the family’s stinging indictment of a number of agencies and a “lack of resources” that Eric so desperately needed to navigate his mental illness.

“It (bipolar disorder) shouldn’t have been a terminal diagnosis but, for the lack of systems in place for Eric, it was,” said Scriver.

“If, when I called the crisis lines, they gave me a solution other than to wait for the police to intervene.”

“If, when I called the police, they had mental health workers to care for him rather than beating him and leaving him in a cold room.”

“If, when I called the Lindsay jail to ensure they were properly caring for his bipolar disorder, they recognized and treated his illness instead of sticking him in general population and not sticking to his medication plan.”

“If, when the chaos of Eric’s mental illness, that brought fear and anger into the lives of his friends and family, they chose to reach out instead of (showing) their lack of understanding.”

“If, when I called the hospital (Peterborough Regional Health Centre) the hour before he died and told them he was too depressed to call himself, that he needs help, they took action instead of mandating Eric would have to call himself.”

“If only.”

Covering the period from May to September of this year, Scriver provided a very detailed timeline of Eric’s downward spiral, and how, in the family’s opinion, those in a position to help did little if anything. Prior, she said, Eric took medications “that caused fogginess and mild depression, among other symptoms.”

“He stayed in that state for years before deciding it might be OK to try and go off them (his medications),” she said.

In July 2022, Eric and Kortney Hilderbrandt married, living in the home they bought together in 2015. Eric’s business, Roter’s Reach Property Maintenance, kept him busy and provided a stabilizing sense of purpose. But, come this past spring, the severity of Eric’s mental illness had shown itself more clearly.

“When Eric was visibly manic, ten of his closest family and friends got together and asked Eric to go to the hospital (PRHC),” recalled Scriver.

“We hoped they would keep him for a few days to level out and get him back on the right medications safely. Reluctantly, Eric agreed to go to the hospital. They ended up prescribing him a low dose of the medication he was previously taking and, at this stage, did nothing to slow the mania. Eric being released and not being admitted fueled his mania, proving to him that he was not manic and that his family was against him by bringing him there (PRHC).”

Noting Eric’s mania “was incredibly obvious — he was behaving erratically with fast, uneven speech and put himself in life-threatening situations,” Scriver said a call to police requesting wellness checks was denied.

“We were told there was nothing they could do. This was devastating news for a family doing all it could to keep their brother, their son, their husband, safe. Unfortunately, the wellness checks being called for by a desperate family led Eric to become extremely mistrusting and angry. He needed to get away from us.”

That he did, says Scriver, stealing their parents’ car and, without a valid driver’s licence, driving to Toronto where he engaged in “risky behaviour” and stayed “at high-end hotels.” For two weeks, Eric spent “all the money he could gain access to, draining accounts for their home as his wife (Kortney) scrambled with the banks to restrict his access.”

Desperate, the family filed a Form 2, which allows police to apprehend and transport someone to a doctor for examination. Toronto police followed up. It didn’t go well.

“Eric was met with aggressive behaviour, cuffed and thrown down, injuring both of his wrists. He was taken to CAMH (The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health) where they assessed him and decided to keep him for observation. To our horror, they released him after two nights and did not proceed with the Form 1 (that allows a doctor to keep someone in hospital for psychiatric care).”

Scriver says Eric was released from CAMH “clearly in a manic state,” adding the family had urged the facility to contact them if and when he was released. That call never came and Eric was on Toronto’s streets for another week, returning home after he had injured himself and was out of money.

“Kortney had installed cameras at their home and on the property and was advised to call police if he (Eric) showed up, and he did,” says Scriver.

“So she did as she was told and called police. Eric was there, gathering his belongings, but seeing the presence of police infuriated him. Triggered by his previous encounters with police, and by his family for calling them, Eric acted out.”

“He ended up vandalizing his and Kort’s home where they had built their life together. This was devastating for all of us, not only because of the destruction but because it truly showed how far Eric was from himself.”

Noting “What Eric needed was treatment, not incarceration,” he was sent to the Lindsay Correctional Centre despite the family’s strong show of support and love at his bail hearing.

“This was a brutal time. Eric would call many times a day, begging to be released. He wasn’t medicated the first week he was in jail and was not given the proper dosage for the rest of his stay. After 30 days, my family agreed we would need to handle this on our own if we wanted anything to get better. My parents took Eric out (of jail) under their surety.”

Released from jail, with family and friends that cared deeply for him in his corner, Eric was “angry, visibly traumatized and still manic.” A follow-up appointment at PRHC saw him declared “mentally unwell” and he was kept in the psychiatric ward for five days.

“Eric was much less manic (when he was assessed) than the previous times we had brought him in, so this was infuriating but, at the same time, a relief. Now he would be assessed and put on the correct medication, but only after all the damage, chaos, jail time, financial impact, the absolute despair of my family and, most importantly, the damage to Eric’s psyche.”

With a follow-up appointment scheduled for six weeks later, Eric was released from PRHC, now taking injections as well as oral medication.

At a family dinner on the Saturday prior to the day Eric took his own life, Scriver says she “could see the pain my brother was in.”

“He could hardly speak. He just kept repeating that he had screwed up his life. I was terrified. I asked if he was suicidal. He said no. I told him I love him as much as my son and my husband. I promised I would help him.”

On Monday — September 25, 2023 — Scriver and her father took Eric to an appointment with her financial advisor in a bid to straighten out the debt he had incurred. When alone with her brother, she noticed he was staring at her.

“Like any sister, I asked ‘What?’ He said he was sorry and that he loved me. At this point, alarm bells were going off. I knew something was wrong. I called Kortney. She said we needed to get him to the hospital and I agreed wholeheartedly.”

“I called the hospital and asked for the psych ward. I told them my brother was unable to speak for himself and needed immediate medical attention. They told me I couldn’t speak for him unless I was with him or he called to give permission. I then asked if there were doctors available for him. They said the psychiatrists were fully booked.”

“I then called my dad to talk about getting Eric to the hospital. Eric answered the phone. I cried and pleaded to let me take him to the hospital. I said ‘I’m just so worried about you.’ He calmly replied “I know.'”

The greatest fear of Scriver and her family was soon realized.

“Within an hour, my brother ran from my father’s vehicle while he was inside a store. He ran to the 115 (Highway 115 in Peterborough) and waited for a transport truck. My father looked for my brother in the parking lot for 45 minutes, refusing to believe the emergency vehicles passing with their wailing sirens had anything to do with why Eric was missing.”

Saying she doesn’t think of her brother’s death as suicide — “My brother would never do that to me or anyone that he loved” — Scriver says she doesn’t feel guilty or regretful. Anger? Indeed.

“I’m angry at the systems in place that did not help my brother once; the multiple opportunities for intervention. If PRHC, Toronto police, Peterborough police, Lindsay Correctional, or CAMH heard the cries of a loving family, or recognized the mental illness consuming my brother, I wouldn’t be standing here. I’d be getting ready to celebrate my brother’s 33rd birthday, which is tomorrow (December 20).”

“I’m so much more than angry or heartbroken that I lost my brother. I feel fear. Fear for my two-year-old son if he’s ever to face mental health issues. I can’t fathom people battling mental health issues alone.”

“If you’re looking for an answer or recommendation of what I would specifically change, or where my family plans to put the money raised to its optimal use, I can’t give that to you now. The problem is too big. What I can tell you is my family and I are forever changed by this nightmare, and I will never stop advocating for my brother.”

For more information about Roter’s Reach Mental Health Awareness, including upcoming events, and to support the not-for-profit association by purchasing merchandise or making a donation, visit rotersreach.ca.