They say learning from past mistakes is one of the most important reasons to study history, but graduate student Holly Benison’s thesis project has her questioning whether we’re doing such a great job of it.

“What does learning from history actually mean?” she asks. “If we have this belief that as time progresses, things are always getting better, why are we still trying to fix the same problems?”

With a bachelor’s degree in history from Bishop’s University in Quebec and graduate certificate in museum management and curatorship from Fleming College in Peterborough, Benison is bringing 19th-century history to social media with a YouTube video series titled “The Backwoods Kitchen” — her thesis project for a master’s degree in public history from Carleton University in Ottawa.

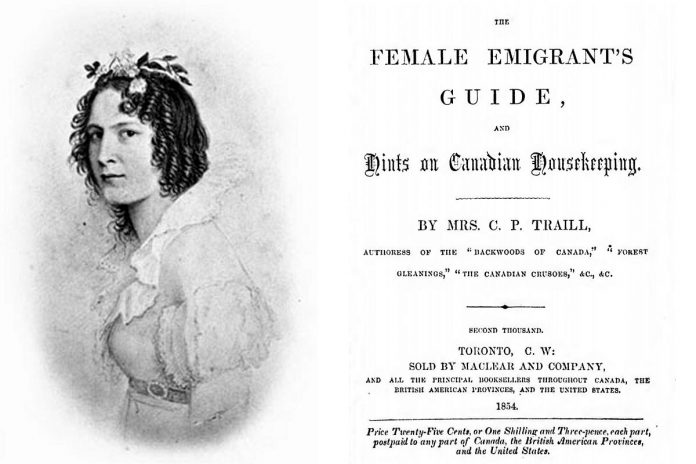

Benison is using the Fitzpatrick House at Lang Pioneer Village Museum in Keene to recreate recipes using tools and techniques outlined in the 1854 book The Female Emigrant’s Guide by Catharine Parr Traill, one of Canada’s most influential writers of the 1800s.

Born in England, Traill and her sister and fellow writer Susanna Moodie emigrated to Canada in 1832 and settled along the eastern shore of Lake Katchewanooka just north of Lakefield. Their brother Colonel Samuel Strickland, who had settled in the area the year prior, is considered the founder of Lakefield (although it wasn’t called Lakefield at the time).

“It has that very unique perspective that this guidebook, cookbook, and survival book was written for a female audience,” Benison says. “It was written in Canada for the specific concerns of our environment — what Indigenous foods we had access to, what won’t grow because the climate is not going to support it, the social customs that were specific to Canada — whereas other cookbooks (of the time) were more general.”

Dressed to the nines in the voluminous dresses of the time period, Benison uses the hearth, dutch oven, and other culinary tools at the Fitzpatrick House — the same ones that would have been used by settlers in the mid-1800s — to create dishes both familiar and unfamiliar by today’s standards, from a pumpkin pie to “mock rice” and, one of her favourites, green corn patties.

Supplying links to scholarly research on the information provided, each episode is bookended with a usually (though not always) satisfying taste test.

“As soon as we let these sites that work go dormant, they’re never coming back,” Benison says, referring to the hearth and other cooking tools at Lang Pioneer Village Museum. “That continued preservation and access and use of those spaces is so incredibly important. We need to remember that as adults, we’re also allowed to have fun and we’re also allowed to play and engage with these spaces. A museum can be a living place. It doesn’t have to be this temple (where we are) quiet and pensive, thinking about the past.”

Throughout the series, Benison is very cautious of recognizing that settlers like Traill were not the first on the land and, without the support of Indigenous peoples, they wouldn’t have held as much of the knowledge as they did.

“In Traill’s book, she already has chapters and pages on Anishinaabe or Mississaugi agricultural practices for wild rice or maple syrup and sugar for hunting,” Benison says as an example. “But, for me, if she writes about it and it’s important to include it, then I’m going to highlight what she says and then do more research and go further with what we now know.”

Benison acknowledges that part of her job as a historian is to critically question the recounts of the time, building on it to supply the best possible information she can to her viewers, rather than a single narrative, as often happens on social media. She notes that while Traill’s writing is considered “progressive,” it certainly holds its limitations.

VIDEO: Green Corn Patties from 1854 – The Backwoods Kitchen Episode #3

“Only now are we trying to make that separation and make that distinction to say that these ingredients come from thousands of years of agricultural development before contact ever happened,” she says about the knowledge of Indigenous peoples. “They were very well-developed agricultural practices with the sort of philosophies of land and environmental sovereignty and well-being that, when settlers showed up, they didn’t know what was happening.”

As an example, in the text, Traill discusses how essential wild rice is and that it should always be in the pantry. But, when it’s being harvested, lots of the grains fall back into the water. Traill and other settlers assumed this to be a lazy practice on the part of Indigenous wild rice harvesters.

“(Maybe) she didn’t know, but there’s a reason for that,” Benison notes. “It’s part of the land-care practice where, if you let the grains fall back, you re-seed the bed so you can get rice next year. Those grains (also) feed wildlife and waterfowl and promotes a healthy ecosystem.”

Further, wild rice is cultivated in shallow parts of the lake but, in the 1850s when the book was written, the land encroachment and infrastructure projects were re-directing waterways and flooding the lakes. Just a few years after publication, Indigenous peoples were being pushed out of their traditional lands, so the availability of wild rice through trade was dwindling and becoming endangered — something Traill wouldn’t have foreseen as it was in abundance while she was writing her book.

“We know what Traill says — which is an amazing source — but when she says ‘This practice is lazy’ or ‘Wild rice is such a great thing’, it also negates that reality that the land was changing in ways that are completely unprecedented,” Benison explains. “We have to see that other side of things, where the land is changing so fast and in ways that settlers probably didn’t realize the impact of those changes.”

Through her project, Benison is not only educating us about 19th-century and Indigenous food practices but is critically reflecting, herself, on what it even means to be a historian.

“The more that I cook in these spaces and the more that I look at these historical recipes, the more that I feel like they’re not so far away,” she says.

Some of Traill’s advice in the book — like how to clean a rug, for example — is still relevant and useful today, and so are the greater discussions and problems being addressed in the text. Benison notes this is especially evident through how the book showcases the “most basic survival food” for the average farmer.

In the first episode of The Backwoods Kitchen, Benison makes a raspberry vinegar which, she explains, is intended to be an affordable wine substitute. In her book, Traill notes that both raspberries and vinegar were inexpensive products.

“The quantity of raspberries that I need would cost me 15 to 20 dollars in the grocery store,” Benison says. “When it comes to food affordability, which is the big thing that she’s addressing in the book, I’m shocked at the fact that none of it is really relevant anymore.”

Benison adds that today, while we are showing concern for knowing where our food comes from, we often don’t have the same access to land and gardens that settlers did to grow our own.

“(Traill’s) advice just shows that cognitive dissonance, in the way that a lot of people assume that as time goes on, things are bound to get better because we’re learning from the past,” Benison points out.

“But if that were truly the case, would we still be experiencing these same challenges? We’re still trying to contend with the same problems, but the structures around those problems are so different that her answers — her solutions — are not solutions in today’s climate.”

Calling attention to these conversations while making the information accessible is one of the reasons Benison chose to share her thesis through social media rather than simply writing a paper.

“It’s that dissemination and sharing of solid scholarship that’s being produced in the field, but making it so that people can actually know where to find it and learn about that topic that maybe they weren’t interested in before,” she says. “For me, physically embodying elements of history is the best way to learn.”

So far, Benison has posted seven episodes of The Backwoods Kitchen on her YouTube channel at youtube.com/ByGollyMissHolly/. Though she is taking a brief hiatus while completing the other portion of her thesis, another five videos will be launched soon, including one all about the Fitzpatrick House and those who occupied it.