When discussing the greatest climate change risks facing the city of Peterborough, many people in Peterborough will think back to the floods and storms that our community has experienced over the past few years, but one more sinister risk for many of our city’s most vulnerable might simply be extreme heat.

Recently, there’s been dialogue among local public health experts and municipal staff about the impact that the urban heat island might have on our city, and the implications I believe are worth discussing.

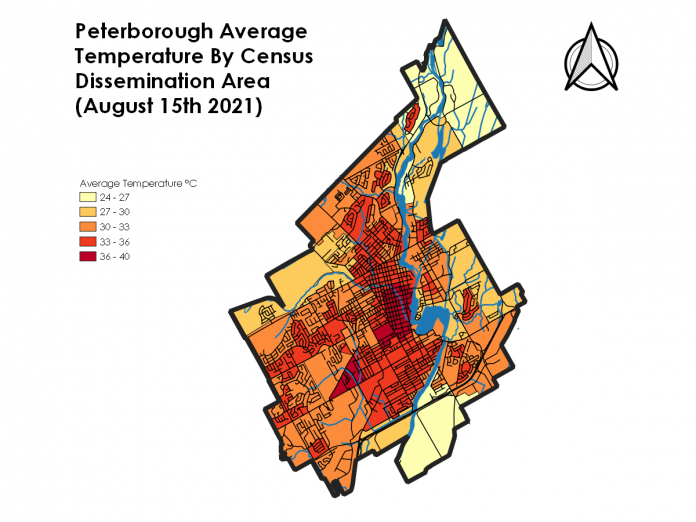

In 2021, I created a map (below) that explores the deviation from the average temperature across all of Peterborough during a typical hot day in August. In that map, we can see the urban heat island at work. A review of the map reveals the downtown core, Lansdowne Street, the Townsend neighbourhood, and several newer subdivisions all clearly have much higher surface temperatures than nearby neighbourhoods.

In the simplest terms, the lack of tree cover exposes hard surfaces such as concrete and asphalt to the sun, which then radiates the absorbed heat back out into the local environment. Neighbourhoods with more trees and less asphalt generally fare better than those without.

Tree cover is one major factor contributing to urban heat, but there are other trends revealed by this map that are worth exploring.

Worth noting is the income disparity that is highlighted by the urban heat island effect. Neighbourhoods with lower incomes, such as Townsend Street or the Tallwood Towers neighbourhood, experience much higher average temperature deviation from the average across the city. The temperature difference can be as much as 15°C in some neighbourhoods.

An average temperature increase of 15°C could place some neighbourhoods in what is known as a dangerous “wet bulb event.” This could all be happening at the same time as other neighbourhoods in the city are experiencing hot, but not life-threatening, temperatures.

If you’ve never heard of a wet bulb event, it is when there is sustained increase in temperature and humidity to the point that the human body loses the ability to effectively regulate its temperature. Exposure to these conditions can lead to death in as little as six hours for those who are unable to move to a colder climate-controlled space or find other means of cooling off. Wet bulb events can actually occur as low as 31°C if humidity is above 95 per cent.

In the city of Peterborough, this could practically mean that individuals who live in lower income neighbourhoods, who are less likely to have access to air conditioning and more likely to have mobility challenges, could have a highly increased risk of extreme heat exposure. With a 15°C surface temperature difference across the city, this could conceivably be happening while citizens in other neighbourhoods are perfectly fine.

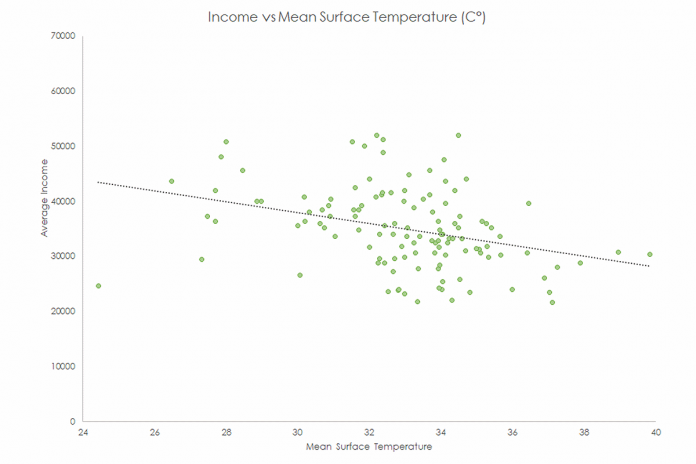

Comparing average income versus mean surface temperature across our city demonstrates a slight trend towards lower-income neighbourhoods experiencing an increased chance of facing increased temperature.

The trend demonstrated by this relationship is strong, but not absolute, so there must be other factors to consider when discussing urban heat island effects, and indeed there are.

As we explore those factors, we will discover potential strategies to mitigate the impact that the urban heat island will have on our community into the next century.

The answers are blowing in the wind

If you’ve lived in the city of Peterborough long enough, you’ll be aware that the wind often blows from the west. These prevailing winds can help us understand some of the heat distribution in our city.

Remember that parks and greenspaces often experience lower-than-average temperatures than areas of concrete and asphalt. Let us consider what happens as the wind passes over these greenspaces. If the temperature of the air is warmer than the surface temperature of a tree that it is passing through, the wind will transfer some of the heat out of the air and into the leaves of the tree.

Each individual tree has an absolutely enormous surface area made up of leaves. This large surface area translates into a huge capacity to exchange heat out of the atmosphere. Neighbourhoods downwind of trees are well positioned to reap the benefits of these massive “heat exchangers,” as the cooler air now has increased capacity to absorb heat from the neighbourhood and convey it away.

This “heat exchanger” effect makes parks and greenspaces are some of our best tools for fighting the effects of urban heat and climate change. It is definitely worthwhile to consider park and greenspace planning strategies in our community that prioritize planting and protecting trees that are upwind of high-risk neighbourhoods.

As far as I am aware, little consideration has been given to this strategic factor when considering our urban forestry plan, and I would like to encourage leaders across our city to keep in mind.

Southern exposure

South-facing slopes can also increase the risk related to heat exposure. Heat that radiates from the sun is more directly absorbed into the concrete faces of buildings and parking lots, especially those that face south.

Large parts of Peterborough are located on a southeast-facing slope. Ten thousand years ago, this large slope was the shoreline of glacial Lake Peterborough, and today offers stunning views of the surrounding countryside. These stunning views carry some risk exposure as well.

The most pronounced exposure to the south is arguably the slopes north of the Parkway Trail on the north side of town. We can clearly see on the urban heat island map a line of census areas that experience higher than average temperatures, possibly due to this southern exposure.

Considering this, it may be worthwhile to prioritize south-facing slopes for naturalization and tree-planting measures across our city. I can already think of several possible locations that may be worthwhile to consider putting some effort into reforestation.

A (cool) river flows through

Many people each summer make the trip down to the Silver Bean in Millennium Park along the shores of the mighty Odoonabii (Otonabee) River. It’s been unofficially dubbed “the little cottage in the city” and for a good reason. The natural surroundings create a welcome retreat from the urban heat radiated from the nearby downtown.

We should consider that the rivers and waters flowing through our city may be one of the greatest tools we have when fighting urban heat. As you take a moment to review the heat map, notice that much of East City is cooler than the west bank. I would argue that, in part, that is due to the downwind impacts of the river.

As wind blows across the river, it deposits warmth from the air into the water to be conveyed away from the city, therefore cooling the city’s east bank — just like a giant natural air conditioner.

This principle combined with several of the other watercourses in our city could provide huge benefits to neighbourhoods badly in need of heat interventions.

Jackson Creek in the Townsend neighbourhood and downtown has been almost entirely covered by buildings and parking lots. A long-term strategy of opening up the creek and naturalizing its shoreline could help keep these neighbourhoods cool, while providing recreational and flood-reduction opportunities.

Other creeks in our community are worth highlighting due to many of the same reasons, including Bears Creek in the north end of our city, or the hidden Brookdale creek roughly following Downie Street.

Urban heat is worth taking seriously. I hope some of you readers can take the time to incorporate some of these ideas into your work or encourage others to do so. Perhaps with your help, we can start to incorporate some of the above ideas into our urban planning strategies and help build a cooler, healthy, and vibrant community for everyone, no matter who they are or where they live.