Social justice and commercial entertainment have always made strange bedfellows. The truth is often too ugly to bear and the penchant for sentimentality is nearly all encompassing.

But the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences love their triumphs of the Human Spirit; and the usual bid for Oscars delicately sashays around the more radical aspects in an attempt to blend into the populist multiplex mainstay.

Is publicly honouring works depicting past injustices meant to ease our sense of liberal guilt, by acknowledging that there was a problem in the first place and that this problem has now gone away?

Or are these works being placed on a pedestal as monuments for future generations to preserve and remember?

In effect, both assessments are accurate. The issue has always been that films depicting grave injustices from the recent past are made to pander to our holiday sensibilities. Films like The Help and the pretentiously titled Lee Daniels’ The Butler may purport to tackle racism, but they are little more than a pandering glaze of tolerant progression come ballot time.

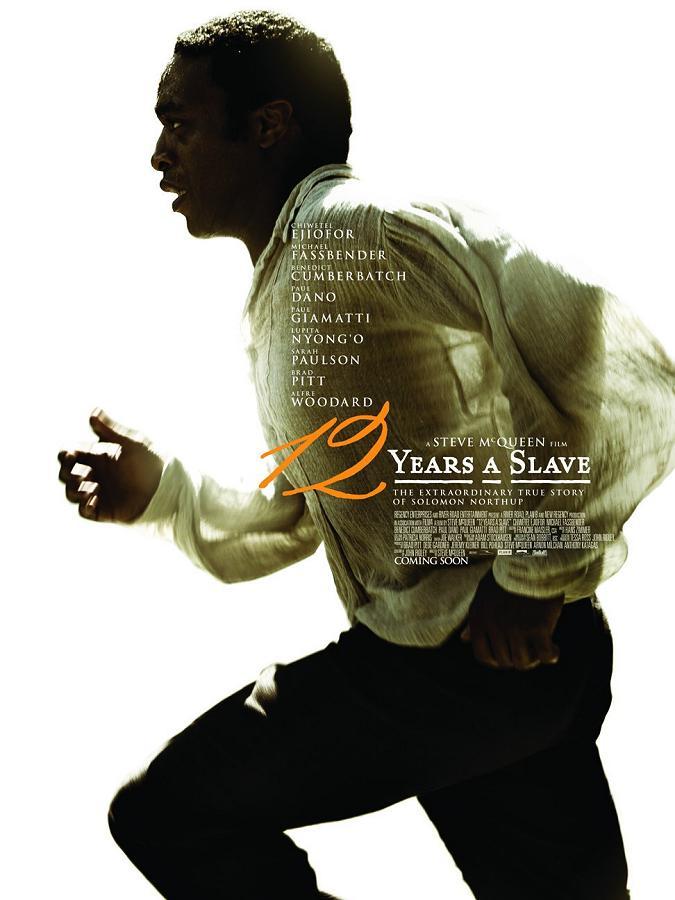

English-visual-artist-turned-filmmaker Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave refuses to be seen but not heard: it is arguably the most honest and visceral depiction of slavery ever committed to celluloid. There is no great love story, no satisfying revenge; there is almost only pure horror in the staggering inhumanity it recalls of America’s Primal Sin.

Early buzz likened McQueen’s to be the definitive film on the topic — the Schindler’s List of slavery films. This is a rather vulgar comparison. Both films are uncompromisingly matter-of-fact in their portrayal of the unflinchingly casual and banal brutality within their respective mise-en-scène, but it is impossible to try and compartmentalize the fathomless anguish inflicted by two of history’s most bewildering atrocities into the parameters of a film — let alone fit them into the same compact category.

McQueen’s work casts an almost absurdly intimate eye on what a human being is capable of enduring to be heard. His debut Hunger nearly wordlessly chronicled the hunger strike of IRA martyr Bobby Sands; his follow-up Shame tragically probed the arctic wilderness that is sex addiction (both films were my favourites upon their respective years of release).

Fears that McQueen had sold out for a stable of A-list sex symbols can thankfully be put to pasture.

12 Years a Slave tells the true story of Solomon Northup (Chiwetel Ejiofor in a stunning, star-making performance), a free black man residing in Saratoga, New York, who is a gifted carpenter and musician living peacefully with his family. Northup is kidnapped and sold into slavery after being promised a lucrative position playing the violin in Washington. Bewildered and shocked at this hideous betrayal, Northup desperately tries to reason with his captors to allow him to return to his wife and children, but his pleas are met with inhuman contempt as he is spirited away into the lion’s den of forced labour.

Bound and alone, struggling to live, Northup hangs horrifically from a tree in a series of shots that feel like they unfold over the course of hours, not minutes. The bustling plantation continues to function while Northup nearly dies in plain sight. An effigy to the elephant of modern social racism — we may look past it, but it is still there, ferocious and writhing.

McQueen’s painterly eye almost compulsively conjures up nightmarish compositions juxtaposed against the dreamlike majesty of the actual antebellum settings in the greater New Orleans area. Using the images of Goya as a reference point, McQueen keeps the camera largely static in the more challenging sections, and wisely retains a neutral and realistic palette that almost gives the sense of documentary.

Fassbender is given monolithic support in his cruelty by a searing Sara Paulson as his Lady Macbeth. Epps’ growing obsession with a young slave, Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o, heartbreaking) drives much of the narrative of the second half of the film. It is a deeply unsettling and exploitative dynamic that is explored here, but it asks the critical question: what is the master without the slave?

It is at this juncture that we briefly become acquainted with another plantation presided over by Mistress Harriet Shaw (a regal Alfre Woodard) who utters the immortal fortune “The curse of the pharaohs is nothing compared to what awaits the plantation class.” Screenwriter John Ridley’s dialogue is frequently peppered with lines of deeply poignant beauty and is accurately fashioned after the then-omnipresent influence of the King James Bible.

Criticism has also been aimed at the notion that we are meant to identify with an atypical hero that misrepresents a legion of disenfranchised people; that we need an individual scale to comprehend a large scale problem. This is valid to a degree, but it misses the key point that the experiences of Soloman Northup are indicative of a bigger picture and that despite the transcendent violence we have been witness to, this is an almost overwhelming work about catharsis and healing.

12 Years a Slave is not an easy film but most certainly a great one. Is it the final word on the subject? Never. A step in the right direction? Absolutely.

12 Years a Slave – Official Trailer

All photos courtesy of Fox Searchlight Pictures