The pandemic has laid bare the ever-widening wealth and income inequality that exists in Canada.

Though flawed, emergency response benefits such as CERB and CRB — the closest thing the country has ever seen to a basic income — have provided an income floor, preventing or alleviating poverty for many Canadians (for those able to access the programs, that is), while also stimulating and stabilizing the broader economy.

In terms of pandemic recovery, basic income has increasingly been a subject of discussion across the political spectrum. As such, support for basic income is growing among parliamentarians and the wider Canadian public.

Much advocacy work continues to be done, and Canadian artists and arts workers — many of whom face unreliable incomes and precarious labour conditions — are proving to be leading voices in ongoing basic income conversations.

In July 2020, over 300 Canadian artists, arts workers, and organizations (including Peterborough-Nogojiwanong’s Electric City Culture Council) published an open letter, signed by organizations representing 75,000 artists, asking Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to create a permanent Basic Income Guarantee.

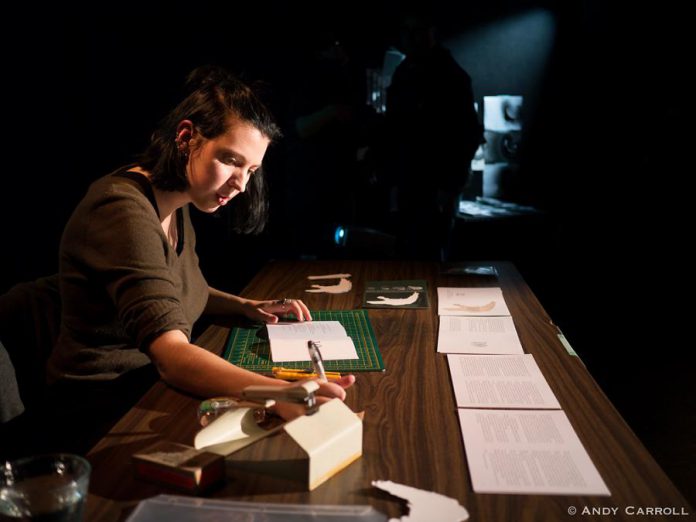

Recently, the Media Arts Network of Ontario hosted two full-day panels called “Basic Income: An Artists’ Commission”, which will inform a report authored by the commissioners for advocacy work ahead of a possible federal election this year.

More than 20 artists from across the country, working within all disciplines, delivered testimonies regarding the impact a steady, fixed income (or lack thereof) has had on their lives and artistic practices during the pandemic.

One of the testifiers, writer and publisher Elisha Rubacha from Peterborough-Nogojiwanong, also happens to be an expert on basic income.

In addition to being a practising artist, Rubacha, who works as a knowledge transfer specialist and civic engagement coordinator for local not-for-profit Nourish Peterborough, advocates for a national Basic Income Guarantee program.

Rubacha has also participated, as both an artist and a panellist, in Precarious: Peterborough ArtsWORK festival (2017) and Precarious2: Peterborough ArtsWORK Festival (2019). Co-presented by Public Energy and Fleshy Flud, both of the month-long multi-arts festivals investigated precarious labour through artistic works, workshops, and community-based panel discussions. The next Precarious festival is slated to occur later this year, with a mix of online and in-person events.

As discourse surrounding basic income becomes mainstream, Rubacha stresses the need for linguistic clarity to distinguish the many nuances to various approaches to basic income programs.

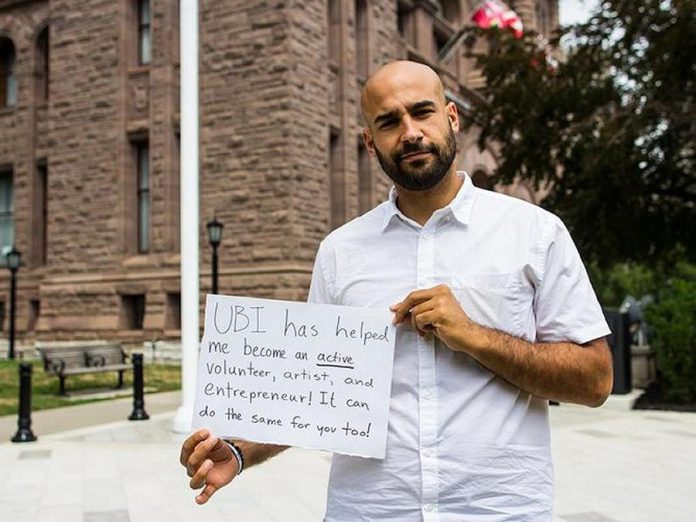

“People use UBI [Universal Basic Income], which is an American import, as an umbrella term, but that’s not what many Canadian advocates are looking for,” Rubacha says.

Instead of a UBI, which would be given to every citizen and then taxed back from those who don’t need it, most Canadian experts are calling for a Basic Income Guarantee (BIG) — a needs-based, means-tested income support program.

For advocates like Rubacha, a UBI model is not feasible for pandemic recovery for artists or others living on a low income, as it would be too slow and too expensive to implement.

“The problem with UBI is that it costs too much up-front,” explains Rubacha. “It’s going everywhere instead of where it’s most needed. Whereas a BIG is income-tested for people living in poverty and then it tapers off, much like the Canada Child Benefit.”

Since the tax system infrastructure already exists, tax-rate increases would not necessarily be required to fund a negative income tax-style Basic Income Guarantee program; in fact, a BIG could actually result in savings for the state.

“We’re currently spending billions of dollars on poverty every year, especially on health care and the criminal justice system,” says Rubacha. “All kinds of health problems are directly related to food insecurity, and so many people are criminalized because they’re living in poverty. Lifting people out of poverty frees up so much money that we’re currently wasting.”

“People want to work. In the Mincome [Manitoba] pilot project, the only demographics that saw a dip in workforce participation were mothers choosing to stay home with their kids and young people choosing to stay in school so they could get better jobs.”

“In the Ontario pilot project, we saw a lot of entrepreneurs,” Rubacha says, referring to the basic income pilot project announced by the previous Liberal government in 2017. The three-year pilot was cancelled prematurely by Doug Ford’s PC government in July 2018, a month after it was elected, citing the program’s high cost as one factor.

“The people who did leave their jobs actually went on to start new businesses and create even more jobs in their community,” she points out.

For artists who face unreliable incomes, a BIG would provide an income floor to help cover the costs of living, freeing their time and energy to create artwork on their own terms. It would give them leverage when faced with unsafe or underpaid work.

A BIG could put an end to the romanticized trope of the “starving artist”, an exploitative framework that currently sees cultural production — a massive economic driver — subsidized by the unpaid work of artists.

The arts and culture sector accounted for $56.02 billion of Canada’s total GDP in 2018. That’s twice as much as the forestry sector at $21.8 billion and nearly 10 times as much as sports at $5.9 billion.

“Artists have been living precariously for generations — we always have — and that’s not something I have a romantic, fuzzy feeling about at all,” says Kate Story, founder and artistic director of the Precarious festivals.

“I don’t create better when I’m miserable and I can’t eat or pay my rent,” continues Story. “Those periods in my life have not been conducive for creative output.”

As Rubacha so eloquently stated to close her testimony on the national stage, “If we continue to accept ourselves as starving artists, we will be doomed to try to create under those conditions.”

This story has been corrected to clarify the difference between Universal Basic Income and a Basic Income Guarantee.