A researcher from Trent University in Peterborough is part of a Canadian team of anthropologists that has used DNA to identify a member of the ill-fated 1845 Franklin expedition — the first member of the expedition to be positively identified through DNA and genealogical analyses.

Dr. Anne Keenleyside, associate professor in Trent University’s anthropology department, along with researchers from the University of Waterloo and Lakehead University, made the ground-breaking discovery, which was recently featured in The New York Times and is making headlines around the world.

By comparing DNA extracted from tooth and bone samples — more than 170 years old — that were recovered in 2013 on King William Island in Nunavut with a sample obtained by a direct living descendant, the researchers were able to confirm that the remains are those of Warrant Officer John Gregory, an engineer aboard HMS Erebus.

“We now know that John Gregory was one of three expedition personnel who died at this particular site, located at Erebus Bay on the southwest shore of King William Island,” says Douglas Stenton, adjunct professor of anthropology at the University of Waterloo.

Stenton, along with co-authors Keenleyside, Stephen Fratpietro of Lakehead University, and Robert W. Park of the University of Waterloo, has published a paper about the team’s research in the journal Polar Record.

To confirm John Gregory’s identity, the researchers obtained a DNA sample from Jonathan Gregory of Port Elizabeth in South Africa — his great-great-great grandson.

“Having John Gregory’s remains being the first to be identified via genetic analysis is an incredible day for our family, as well as all those interested in the ill-fated Franklin expedition,” Gregory said. “The whole Gregory family is extremely grateful to the entire research team for their dedication and hard work, which is so critical in unlocking pieces of history that have been frozen in time for so long.”

In 1845, Captain Sir John Franklin led an expedition of 129 sailors on two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, to traverse the last unnavigated sections of the northwest passage in the Canadian Arctic and to record magnetic data to help determine whether a better understanding could aid navigation. In late 1846, both ships became icebound in Victoria Strait near King William Island in what is today Nunavut.

The crews abandoned the ships in 1848, by which time Franklin and nearly two dozen others had already died. The survivors, led by Franklin’s second-in-command Francis Crozier and Erebus’ captain James Fitzjames, set out for the 400-kilometre march to the Canadian mainland. All eventually perished.

Since the mid-19th century, skeletal remains of dozens of crew members have been found on King William Island, but none had been positively identified. To date, the DNA of 26 other members of the Franklin expedition have been extracted from remains found in nine archaeological sites situated along the line of the 1848 retreat.

“Analysis of these remains has also yielded other important information on these individuals, including their estimated age at death, stature, and health,” says Keenleyside, who has been researching the Franklin expedition since 1993, analyzing skeletal remains of more than a dozen crew members recovered from King William Island to construct biological profiles that include information on age, sex, ancestry, stature, and features such as trauma and pathology.

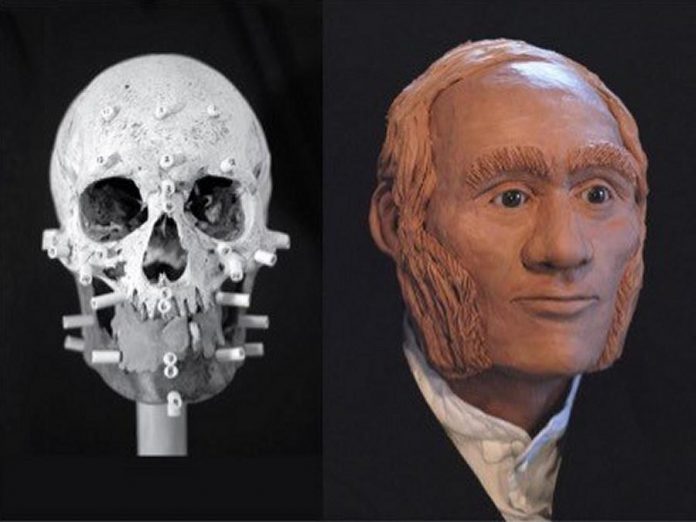

Keenleyside was also involved in the facial reconstruction by forensic artist Diana Trepkov of two of the crania found at the King William Island site, and started taking DNA samples for analysis.

“Once we had this database our next step was to seek out living descendants of the crew and ask them if they would be willing to submit buccal samples for DNA analysis to try and identify the remains found on King William Island,” Keenleyside explains. “We are truly grateful to the Gregory family for providing DNA samples in support of our research, and we encourage other descendants of the Franklin expedition crew to reach out to our team.”

Prior to the DNA match, the last information about Warrant Officer John Gregory’s voyage known to his family was in a letter he wrote to his wife Hannah from Greenland in July 1845 before the ships entered the Canadian Arctic.

The letter ends with the words “Give my kind Love to Edward, Fanny, James, William, and kiss baby for me — and accept the same yourself.”

The research was funded by the Government of Nunavut, Trent University, and the University of Waterloo.