This week, senior political officials from nations around the world are at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland. This “Conference of the Parties” (COP for short) is the 26th annual meeting of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

There’s a lot at stake with COP26, so I asked three local experts for their perspectives on COP26 and why it matters both globally and locally.

“The COP meetings began almost 30 years ago at the 1992 Rio Summit, when the UNFCCC was negotiated,” explains Stephen Hill, associate director of the Trent School of the Environment. “The goal of the UNFCCC has always been to commit to stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions. In their language, the goal is to prevent dangerous human interference with the climate system.”

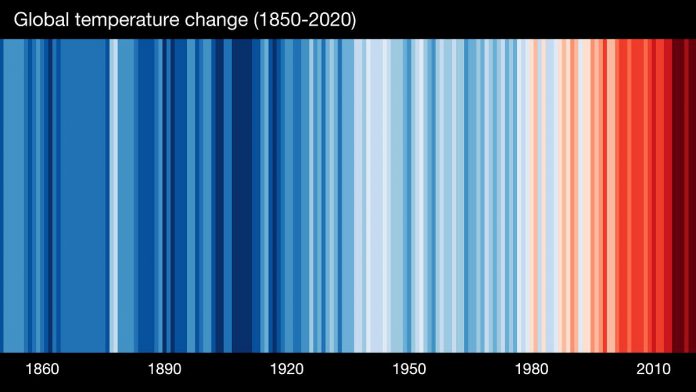

Hill shares an analogy to explain this. Think of the entire planet as a bathtub that can only hold so much greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) before it overflows into “dangerous” territory. That overflow point is 1.5 to 2 degrees of global warming.

“There are two parts to preventing dangerous global warming,” Hill says. “First, we have to stabilize the GHG level in the bathtub by reducing the flow to a trickle. The modelling shows we must act now. That means reducing emissions at least 45 per cent below 2010 levels as soon as possible, ideally by 2030.”

“The second part is figuring out how to drain the bathtub. Reducing emissions to near zero is crucial but not enough by itself. That net-zero target requires capturing and storing significant amounts of carbon, both with natural and technological solutions.”

VIDEO: Earth To COP

The intention of the 2015 Paris Agreement (COP21) was for each nation to commit to reductions they felt they could achieve, not to stabilize GHG levels globally.

Brace yourself: here comes some doom and gloom. The global flow of GHGs into the atmospheric bathtub continues to increase — even during COVID-19 — and has increased every year since the 1992 UNFCCC agreement was signed.

Today world leaders are gathering at COP26 to evaluate the progress of each nation and set another round of ambitious reductions targets.

“Even with our late start, it will take time to turn a big ship like our energy system around,” Hill points out. “Emissions don’t go down that quickly. What we need to see first are domestic policies and accountability measures that back up the commitments nations make at the COP.”

“The Paris Agreement, along with public pressure and youth activism, acted as a catalyst for recent political action. In the last five years, climate politics have changed tremendously in Canada. For the first time, we now have credible policies and plans.”

Stephanie Rutherford, associate professor in the Trent School of the Environment, agrees.

“The plans that the Canadian government has put forward in the last year aren’t perfect, but they’re the first I’ve seen with any kind of teeth,” Rutherford says.

“We need to be asking for real, measurable targets, enforcement mechanisms, and plans for ratcheting down emissions throughout the course of the policy over many years. There are also lots of environmental non-governmental organizations, like GreenUP, that have decades of experience and knowledge on these issues that the government could leverage going forward.”

Rutherford’s research focuses on environmental justice and multi-species perspectives. While previous COPs have tended to overlook the importance of habitat and ecosystem protection and restoration, this year’s COP looks different.

“The climate crisis is not separate from the biodiversity crisis,” explains Rutherford. “These are interlinked crises. You can’t have a conversation about climate change without also talking about habitat loss and mass extinction.”

According to Rutherford, the stakes are high for Canada.

“Climate change is an issue not only of the environment and the economy, but also of justice and equity,” she says. “First Nations people in Canada have disproportionately felt the impacts of climate change, and there is a lot at stake in the relationship between climate change and reconciliation.”

“Canada was once known as an environmental leader, but no more. We take a lot of body blows at these COPs because we make big promises but with almost no follow-through. The world is waiting to see us actually act. It will not be easy. There are jurisdictional disputes with some provinces. Historically, Canada has also not pursued the kind of policies that prioritize habitat protection, ecosystem integrity, and treaty rights before resource extraction. We have work to do.”

Like Canada, Peterborough (once known as “The Electric City” as it was the first town in Canada to use electric streetlights in the late 1800s) likes to stake claim to a reputation for innovation and environmental leadership.

“As a community, we should be thinking about how we will live in this changing world in a low-carbon economy,” Hill says. “We should be anticipating what this means for jobs, businesses, housing, education systems, and transportation systems. There are pockets of truly amazing leadership in Peterborough, but we are falling behind other communities.”

One of those pockets of amazing leadership is the Endeavour Centre, the Sustainable Building School.

“I am most excited and also most frustrated about the potential of the building industry for emissions reductions,” shares Chris Magwood, founder of the Endeavour Centre. “There’s so much talk about incremental reductions in emissions over decades, but with buildings it could be way more than incremental. We could literally — right now in the next few years — reverse the climate impact of buildings.”

“COP26 is the first time that buildings and the building industry have had a central presence. There is a net-zero demonstration house at COP26. For decades, the Endeavour Centre has been trying to demonstrate the potential of low-carbon building approaches. The new forensic crime scene building at Trent University is a net-zero carbon storage building. This and other local projects are world-leading demonstrations of what’s possible right now. These approaches exist, but it seems people do not recognize them as the major precedent-setting examples that they truly are.”

Magwood believes municipalities are going be the leaders in this area, even though building codes are written at the national level.

“Duoro-Dummer had the very first low-carbon building incentive program in North America,” Magwood notes. “The Endeavour Centre is working with Nelson in B.C. right now on something like that. We start working next month with Vancouver and Toronto looks on the verge of doing something. Municipalities don’t have power over building codes, but there seems to be the most willingness to move quickly at that level.”

“I would hope that politicians start to see the potential for becoming the world leader in manufacturing biogenic building materials,” suggests Magwood. “Canada is rich in all the best sources of raw materials, and most of these resources are available in rural areas like Peterborough. We are smart enough to manufacture here. We just need the push to do it and scale it up. There’s a compelling economic and environmental case for doing this.”

To learn more about the global significance of COP26, visit the UN Climate Change YouTube channel.

For more information on the climate action resources available locally, now, visit greenup.on.ca/climate-action-resource/.