GreenUP encourages people to connect with nature and appreciate the health and history of local watersheds. This guest-authored story is the first in a series about a 2021 paddling trip from the Odenaabe (Otonabee) River downstream to Lake Ontario. One of the inspirations behind the trip was to connect with the watershed, its history, and the traditional migration of the Atlantic salmon along this route.

This first story in the series is written by Paul Baines, Blue Community Coordinator for the Federation of the Sisters of St. Joseph. This program protects water as a human right, shared commons, and sacred gift.

I often hear that ‘modern’ people have lost their connection to nature. Conditioned air, paved paths, GPS, illuminated nights, 4K screens — what we call ‘a lifestyle’ these days. But with every inhale, every drink of water, every digital switch or analog button we press, and every cushioned stride we take, we are always connected to the living earth. What many of us have lost or are at risk of losing (including myself) is our sense of connection to nature.

I live on the Odenaabe (Otonabee) River and have a job that aims to connect people to their watershed. I’ve often thought about who and what is downstream from me, the history of this territory, and how we all connect to water.

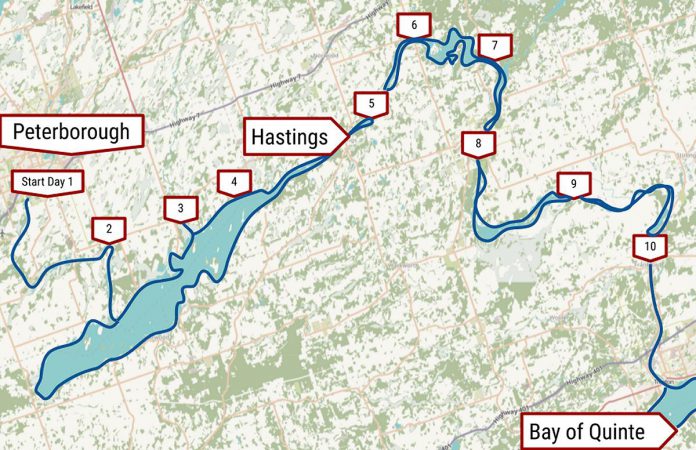

Last May, some friends and I took a paddling trip over 150 kilometres from the Odenaabe River down to the mouth of the Trent River where she meets Lake Ontario. This adventure was planned as 10 separate day trips over the spring, summer, and fall. In October, we reached the Bay of Quinte and finished on the shores of Prince Edward County.

For each trip, between two and nine friends joined with their canoes or kayaks. In total, 16 of us (and two dogs) took part in at least one leg of this journey. Here is a map of our route.

We planned each route attuned to the elements — our larger guide. Dry weather, sunshine, low winds or downwind, rest stops, swimming options, and daily total paddle distances. As settler-immigrants in Canada who have all lived in this watershed for several years, most of us had never paddled and pondered the southern Odenaabe, Rice Lake, or the Trent River.

Most other people we saw on the waters were in motor boats: fishing boats, pontoon boats, speed boats, and even houseboats. With our human-powered pace, floating and shoreline lunches, wildlife and town life explorations, and swim dips, I felt right at home within this larger water body.

It was often tricky to find public access spots to launch, since roads were mainly built to access private property. Everyone loves living by the water. We saw families and retirees with raised Canadian flags on the shoreline along with tall silver maples, fresh layers of ferns, and statuesque great blue herons.

I was able to sense the multiple relationships that the waters invite: home, recreation, transportation, heritage, hydration and sanitation, tourism, play, refuge, and admiration.

We would often open or close our paddle day with a simple ritual of intentions and gratitude.

Carried by the river’s measured flow, we portaged around or navigated through 18 historic locks. My lungs filled with the blue expansiveness of Rice Lake, my ears were tickled by the many birdsongs in the thick marshes near Keene, and my body and boat swayed within the waves caused by high winds and motor boats.

I also felt a numbness and even sadness when the river was channelized for marine navigation, water level control, and electricity generation.

One of the most dramatic ways the river was shaped was in 1910 at giant flight locks near Healey Falls (locks number 16 and 17). Here, the Trent River is split into three parts: one part lock, one part hydro dam, and one part into three huge metal tubes that are each five meters wide and 150 meters long.

These tubes manage the river into a large hydro generating brick building. It’s impossible for me to sense what this place would have looked and felt like over 100 years ago with its bubbling and beating rapids and its unbroken waterfalls.

One sense I carried throughout this experience was the ghost of the Atlantic Salmon. For over 12,000 years, these silver ‘kings of fish’ embodied these waters and fed the bodies and spirit of the Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg who consider themselves to be salmon people — the traditional people and caretakers of this territory.

But within 100 years of steadfast European settlement, values, and impacts, the Atlantic Salmon became extinct to these waterbodies. Since the 1890s, no one has been able to celebrate the salmon’s upstream return each fall season — a homecoming.

I see a small section of the Odenaabe from my home window. This trip extended my attention and senses. I can now better understand a much larger shoreline and storyline.

I hope you can extend your senses within this watershed as the summer months approach. Follow this journey again in June as Jenn McCallum enriches our understanding and appreciation of this watershed’s vitality.