At 9 p.m. on Sunday, October 23rd — the 50th anniversary of the death of Chanie Wenjack — CBC will be broadcasting Gord Downie’s animated film The Secret Path.

Trent University invites the community to attend a free screening of the broadcast at Wenjack Theatre, named after the Indigenous boy who died after escaping from a residential school. The screening will be preceded by a reconciliation panel discussion.

“We are pleased to be able to show the film and discuss the legacy of residential schools as well as the many efforts underway to help to heal,” says David Newhouse, faculty member and chair of the Department of Indigenous Studies at Trent University.

“It is through understanding our history that we take steps to ensure that this does not happen again. We all have a part to play in reconciliation. It starts with educating ourselves.”

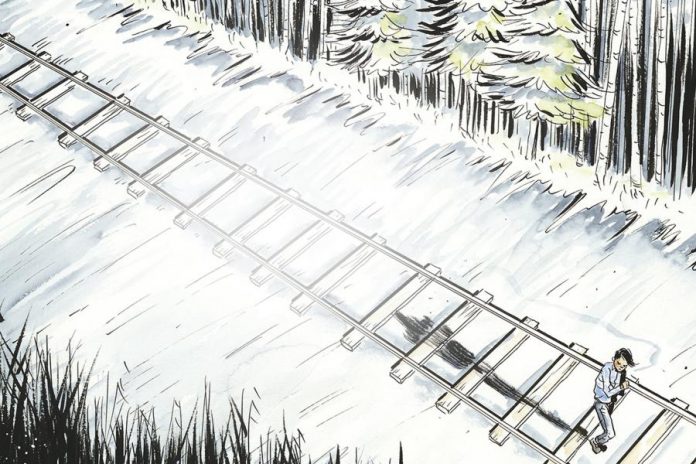

The Tragically Hip’s Gord Downie began his Secret Path project (secretpath.ca) after learning from his brother Mike about the the story of Chanie Wenjack. Gord wrote 10 poems, which grew into 10 songs that Gord has recorded as an album. Gord and Mike presented the songs to comic artist Jeff Lemire for his help illustrating Chanie’s story in an 88-page graphic novel.

Downie’s music and Lemire’s illustrations inspired The Secret Path, the animated film to be broadcast by CBC in an hour-long commercial-free television special on Sunday, October 23rd at 9 p.m. (and live streamed at cbc.ca/secretpath).

VIDEO: “The Stranger’, the first full chapter and song from The Secret Path

“Chanie haunts me,” Gord writes in a statement. “His story is Canada’s story. This is about Canada. We are not the country we thought we were. History will be re-written.”

A panel discussion will take place before the screening at 7 p.m. The discussion will cover Canada’s history of residential schools, their lasting impact, and how to move forward through reconciliation.

Panelists include Shirley Williams (Elder, Residential School Survivor, and Professor Emeritus at Trent University), Dr. John Milloy (Special Advisor to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and Professor Emeritus at Trent University), Karissa Dawn Martin (an Indigenous Studies & History student at Trent University), and Liz Stone (Executive Director of Niijkiwendidaa Anishnaabe-Kwewag, a not-for-profit organization in Peterborough delivering counselling and healing services for Indigenous peoples).

The discussion and screening take place at Wenjack Theatre, named after Chanie Wenjack. When construction began on Otonabee College at Trent University in 1973, a group of student leaders from the Indigenous Studies department lobbied for the college to be named in Chanie’s honour. The campaign spearheaded by student leaders led to the naming of Trent’s largest lecture hall as the Chanie Wenjack Theatre.

The community is welcome to attend the panel discussion and screening, but are asked to RSVP on Facebook.

The story of Chanie Wenjack

In the fall of 1963, Chanie Wenjack was taken away from his family — his parents, sisters, and two dogs — at Ogoki Post on the Marten Falls First Nation in in northern Ontario and forced to live 600 kilometres away at the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario.

The Anishinaabe boy was only nine years old and understood very little English. Around 150 other Indigenous children lived at the school, which was run by the Women’s Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church in Canada and paid for by the federal government.

The children lived at Cecilia Jeffrey and attended classes at schools in Kenora. Chanie (who was misnamed Charlie by his teachers) struggled to learn English and arithmetic and had to take remedial classes.

Chanie had previously never tried to run away from the school but, after three years, he had had enough. On Sunday, October 16, 1966, Chanie and two of his friends, brothers Ralph and Jackie MacDonald, decided to leave. Chanie told his friends he wanted to see his father.

It was a sunny and mild afternoon, so the three boys left wearing only light clothing. They travelled north through the bush using a “secret path” known to children at the school. They headed for Redditt, a railroad stop 32 kilometres north of Kenora and 48 kilometres east of the Manitoba border.

They had to stop frequently as Chanie was in poor health (a post-mortem would show his lungs were infected at the time of his death). While they were walking, Chanie found a CNR schedule with a route map in it — but he didn’t know enough English to read it.

More than eight hours later, the boys arrived in Reditt. A local white man the MacDonald brothers knew took the exhausted boys in for the night. Early the next morning, the boys walked a short distance further to the cabin of Charles Kelly, an uncle of the Macdonald brothers, who let them stay.

Later that same morning, Chanie’s best friend (who had also run away from the school and was another of Kelly’s nephews) showed up. Among this family reunion, Chanie was considered “the stranger”.

On Thursday, Kelly took his nephews up to his trapline by canoe, leaving “the stranger” behind. Chanie told Kelly’s wife he was going to walk the five kilometres to the trapline, and she gave him some matches in a little glass jar and some food.

Chanie made it to the trapline and stayed overnight but, after Kelly told him he’d have to walk back to Redditt, Chanie said he was going to walk home instead. Kelly showed him how to get to the railroad tracks and told him to ask railroad workers along the way for food.

Over the next 36 hours, Chanie attempted to walk the almost 600 kilometres home. All he was wearing was a cotton windbreaker while he faced weather that included snow squalls, freezing rain, and temperatures between –1° and –6° C. He only managed to walk 19 kilometres before dying from exposure.

When a railway engineer found Chanie’s body, he was lying on his back in soaked clothing and had bruises on his shins and forehead, presumably from falling.

Chanie’s story was also told in a Heritage Minute released earlier in the summer by Historica Canada. The script for the Heritage Minute was written by author Joseph Boyden, who received an honorary degree from Trent in 2014, and the historical advisor was professor emeritus, Dr. John Milloy (who will be part of the panel discussion on Sunday).

VIDEO: Heritage Minutes – Chanie Wenjack