At 23, Katie Brown has spent more time than most in the shadow of death, working with and learning about some of life’s greatest challenges during the course of her co-operative placements as an undergrad student in the Child, Youth and Family program at the University of Guelph.

Among five transformative experiences was her time at a Children’s Hospice in Ottawa where she gained an intimate understanding of the immense pressure families feel when a child is dying.

With partial support from the 10th annual Nexicom James Fund Golf Classic on June 5th, Katie will explore the subject further as she prepares for a new research path focused specifically on the impact a child’s death from terminal disease has on siblings.

She was drawn to the field after falling in love with the Child Life Specialists at Toronto’s SickKids Hospital where she began treatments for newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease when she was barely a teenager. The entire focus of these specialists is on the children, helping them understand what they can expect from the hospital experience and offering them as much choice as possible in situations where control is often elusive.

“They really walk them through what’s going to happen in the hospital and be with them from beginning to end,” Katie explains. “I really fell in love with them and from there I wanted to be a Child Life Specialist.”

With great persistence, she secured the co-op placement at the Ottawa hospice and her life was transformed. There were incredibly difficult days but also amazing opportunities to support children and families and help them make the most out of every second they have together.

It was here that she first encountered the sibling perspective, she says, “and I was struck by the amount of people wanting to help, but the fact was there wasn’t a lot of research into siblings. Yes, we definitely need to focus on the (sick) child and the parents for sure … but at some point we need to look at survivorship for children because when they’re little and they lose a sibling, that’s going to continue to affect them for a very long time.”

Rebecca Birrell, who will share her unique insights at the Nexicom James Fund Golf Classic, is all too familiar with the depth of loss felt when a sibling is taken from this life far too early.

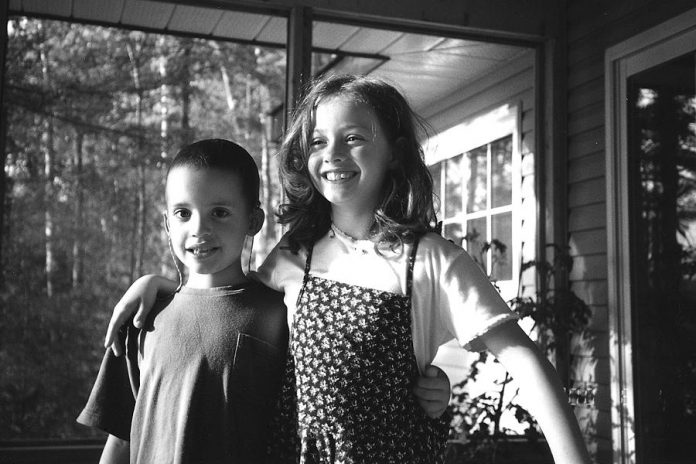

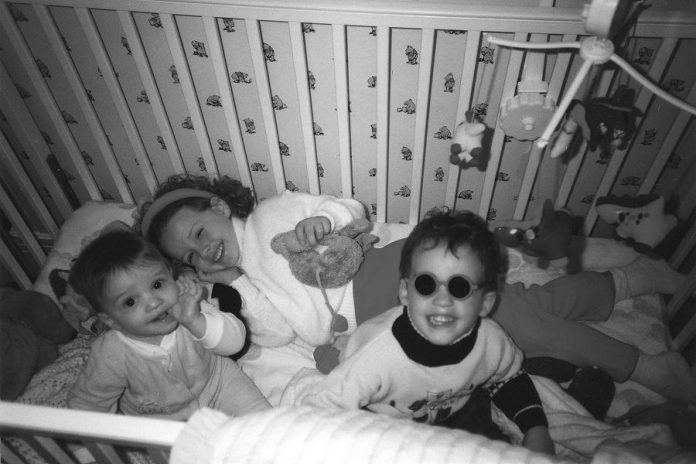

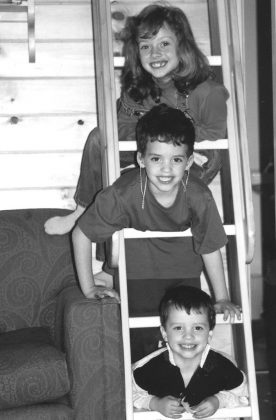

In 2001, when Rebecca wasn’t yet 10 years old, her brother James died from a rare and little-understood childhood cancer, neuroblastoma.

The fund created in his name has since raised millions to support research, while in the past 10 years the Golf Classic has helped support hundreds of loved ones facing the disease. When Rebecca and her other brother Ben were little, however, there was practically nothing by way of specific support.

“I don’t think I ever knew what to expect,” Rebecca says, looking back to the terrible experience of watching her brother and family struggle in the face of hope and despair with the ultimate tragic end to follow. “I guess I kind of had the unconscious assumption that as I grew up, what was in the past would stay in the past and it wouldn’t affect me growing up.”

She had no idea that she, like so many young people who’ve lost a beloved brother or sister, would be at risk of serious depression or other mental health challenges. Looking back, that knowledge would likely have had an immense impact in her formative years.

She may have recognized the signs earlier when depression first struck in her mid-teens; she may have been able to articulate the internal struggle rearing itself and felt compelled to seek help earlier.

“I had no reference point for what depression was or what the symptoms were,” Rebecca recalls. “I just didn’t know at first what I was experiencing and then when I figured it out, how to then approach people and say ‘ I think I’m experiencing these symptoms, I think I need help, but I don’t know what I need.’

“You get to a point where you know you need help but you don’t know what to ask for,” she says.

There was guilt, of course, because she knew how deeply her parents felt the loss of James and she didn’t want to burden them with her own struggle. She didn’t want them to feel that anything was their fault or blame themselves. She wanted to protect them from the weight she carried.

She never blamed her parents, but she does suggest a deeper lack of preparation and understanding in society in relation to trauma, loss, and mental health existed then and still does today. Things are improving, she says, but there’s a long way to go and the work Katie will begin at the University of British Columbia this fall is one more positive step towards helping young people prepare for an experience like Rebecca’s.

“While the emotional and psychological effects on siblings of children with neuroblastoma is very evident to families and friends, there has been little research on what the specific effects are and how we can develop and mobilize resources to help siblings and their families,” says Dr. David Kaplan, Head of Research with the James Fund for Neuroblastoma Research at the Hospital for Sick Children.

“The goal of this unique collaboration between the University of British Columbia, SickKids, and the James Fund will be to perform the necessary research to develop the tools and resources that will help siblings throughout their lives to manage, cope, and thrive.”

Under the supervision of Dr. Judy Illes, Professor of Neurology and Canada Research Chair in Neuroethics, and Dr. Tim Oberlander, Medical Lead in Complex Pain Service at BC Children’s Hospital and a professor in UBC’s Department of Pediatrics and School of Population and Public Health, Katie will study the impact on siblings who’ve specifically lost a brother or sister to neuroblastoma or brain tumours.

The Nexicom James Fund Golf Classic, which is focused entirely on family support for neuroblastoma families, has offered a $5,000 grant this year and next to support this work.

It will be a complex study based in large part on in-depth interviews, but if it could be distilled to one easy reference point, Katie says she hopes to identify some of the key, unanswered questions a young person asks when faced with the mortality of their beloved.

Ideally, the study will lead to the creation a template of sorts to help guide young people through the tragic experience they’re facing and prepare them for future challenges that are almost sure to arise.

The impact of such loss, Rebecca says, “doesn’t go away and we shouldn’t expect it to.”

Perhaps this study, created in the wake of her brother’s legacy, will help others come to this realization, and for that Rebecca is grateful.