Local author Barbara Mitchell has written the first-ever biography of the 18th-century Hudson’s Bay Company surveyor — and one of her ancestors — Philip Turnor.

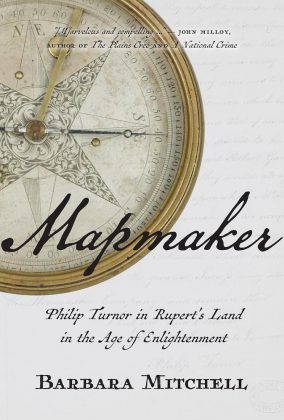

Mapmaker: Philip Turnor in Rupert’s Land in the Age of Enlightenment tells the story of Turnor and his Cree guides who, for 14 years, travelled 25,000 kilometres by canoe and by foot through Rupert’s Land.

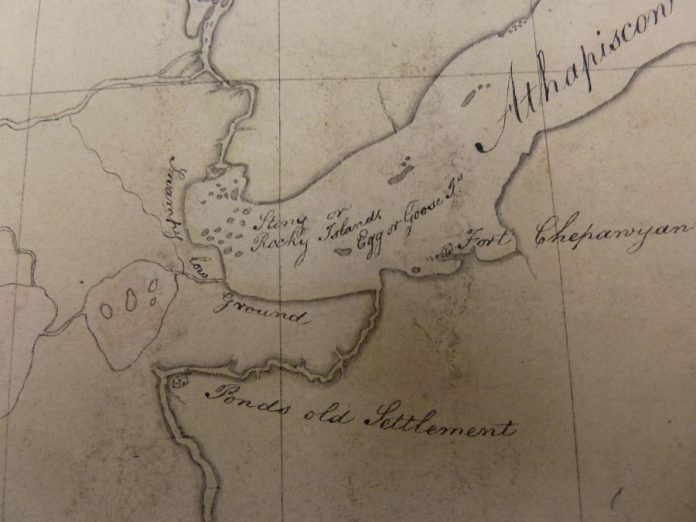

Between 1778 and 1792, Turnor produced 10 maps, culminating in his magnum opus in 1794: a map that was the foundation of all northern geographic knowledge at that time. He also taught British-Canadian fur traders and explorers David Thompson and Peter Fidler how to survey.

Rupert’s Land was a vast territory in British North America encompassing the Hudson Bay drainage basin (what is now all of Manitoba, most of Saskatchewan, southern Alberta, southern Nunavut, and northern parts of Ontario and Quebec, as well as parts of the northern United States), over which the Hudson’s Bay Company had a commercial monopoly in the fur trade for 200 years (from 1670 to 1870).

The Hudson’s Bay Company had complete control of the territory, establishing forts and trading routes, with little regard for the sovereignty of the many Indigenous peoples who had lived there for centuries. Cree, Assiniboine, and other Indigenous peoples (as well as the Métis) supplied the company with furs, acted as middlemen, or were directly employed by the company.

Because of the close economic relationship with and dependency on Indigenous peoples, many senior officers of the company also married Indigenous women. Such was the case with Philip Turnor, who had a Cree wife. At a family gathering, Mitchell discovered she was one of their descendants and was intrigued (see the excerpt from the book below)..

Because Turnor’s journals are very technical and contain no personal information (for example, he never mentions his Cree wife), Mitchell intersperses the biographical information in the book with her own narrative, including genealogy and her research expeditions, to bring Turnor’s story to life.

“Mitchell’s style allows the reader to get up close and personal with both the author and her subject, despite Turnor’s bloodless journal notations,” writes Charlotte Gray in her review of the book in The Globe and Mail. “She brings to life the killing cold of the winters, the insufferable mosquito swarms and the near starvation her ancestor faced, as well as her own the thrill of donning white cotton gloves and unfolding a two-century-old map.”

Mitchell will be launching her book at the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough on Thursday, November 2nd, from 5 to 8 p.m. The free public event includes a complimentary tour of the museum at 5 p.m. and a reception at 6 p.m., followed by a talk by Mitchell at 6:30 p.m. Copies of the book will be available for purchase through the museum’s gift shop. The book is also available at major book retailers and online.

In addition to her latest book, Mitchell is the co-author of a two-volume biography of W.O. Mitchell, Beginnings to Who Has Seen the Wind and The Years of Fame. She has also written a doctoral dissertation on the biographers of Charlotte Brontë and has published several biographical essays. For many years, she taught English Literature at Trent University. Mitchell lives in Otonabee with her husband Orm Mitchell.

An excerpt from Mapmaker: Philip Turnor in Rupert’s Land in the Age of Enlightenment by Barbara Mitchell (University of Regina Press, 328 pages, $39.95)

Prologue

Discovery, 24 October 1992

I knew nothing of my family lineage beyond my grandparents, but on this day in 1992 my family multiplied astronomically. I was forty-eight years old.

It was Thanksgiving — the annual family gathering of the eastern branch of the Goff family. Bob, my uncle by marriage and an amateur genealogist, brought a family tree he had been working on for several years. He unfolded it and tacked it on the wall-it was five feet wide, three and a half feet high. A hundred names, with their birth, marriage and death dates, spread out and down the wall. I began with my mother, Dorothy Goff, and her siblings, two of whom, Anna and Vivian, were at the unveiling. I moved upstream through the Goff parents, to the Loutit and then the Harper tributaries, to Joseph Turner Sr., and finally to the source, Philip Turnor, the first name on the chart. “Born in England in 1751,” I read, he was a mapmaker who “produced the first good maps for the company” and who “took his Indian wife back to England.”

That day I discovered a wealth of information I had never known: I was a sixth generation Canadian; I had Orkney-Scots connections as well as English; my ancestors worked in the fur trade; Philip Turnor, whose name I had never heard before, was a significant figure in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s history. And I had Cree roots. Philip Turnor, my great-great-great-great-grandfather, had come to Rupert’s Land in 1778 from Middlesex, England, as a surveyor, in fact the first inland surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company. His Cree wife was my great-great-great-great-grandmother.

My uncle Bob recalled the day he was checking the 1901 Canadian Census records and discovered “Cree” listed as my grandmother’s ancestry. Aunt Anna and Aunt Vivian were astonished that they had not known this about their own mother. When I questioned them, Aunt Anna reported, “No one ever spoke of it. It never occurred to me that she was Cree.” Aunt Vivian agreed, “If Mother did know about her Cree ancestry, she didn’t say. I wish I had asked her more.” In fact, my grandmother was of mixed heritage. Her grandfather, John Low Loutit, and her great-grandfather, James Harper, had been born in Rupert’s Land to Orkney HBC servants and Cree women.

So, in 1901 when my grandmother was nineteen and still living at home with her parents in St. Andrew’s Parish (Lockport, near Selkirk, Manitoba), it was acknowledged and recorded that she was Cree, but in 1904, when she married an Englishman, that was kept quiet. She did however mention her Cree ancestry to her male children, Barney and Haig. But, like their mother, they did not discuss it openly in the family.

Aunt Anna recalled that there were “always Cree women around. They would bring their lard pails full of saskatoons to Aunt Jennie’s and sit down for tea.” As young girls my aunts absorbed more than they realized. One New Year’s Day on a phone call, my Aunt Vivian recalled hearing a New Year’s greeting in Cree when she was a child. “Happy Noot Shey,” she said to me. She apologized for her attempt and said she did not know how to spell these words. I asked what else she remembered, and she began counting in what she thought was Cree: “Hanika, banika, dib boose, day”-and she continued to twenty. Although I have not been able to identify her numbering as either Cree or Bungee, a Red River dialect, my questions had awakened in my aunt some long-ago memories of hearing an Indigenous language being spoken by her family and friends.

My aunts recalled for me various traditions of their Cree-Scots upbringing that were practiced in the family during the 1930s. One of their aunts made bannock on top of the old cook stove, and my grandmother told her children stories about the place they went during the summer months, which they lovingly called Buttertown. It was not truly a town, only a pasture area out on their land a few kilometres away where they brought the cattle to graze during the summer. It was one of the great pleasures of her young life, my grandmother told her daughters. They picked berries-wild strawberries, saskatoons, and high bush cranberries. The women made red and purple jellies for the winter and churned butter, which they stored in gallon granite crocks and placed in a hole, dug in the ground, so they would stay cool in the hot prairie summers. Pound blocks would be measured out in a butter pat to sell to their neighbours and relatives.

Unfortunately, this was all my aunts could tell me about this side of my family. The furthest back they could go was to my great-grandmother, Nancy Ann Harper.

Philip Turnor was just as much a mystery to them as he was to me.

***

Work prevented me from pursuing my family history for a number of years, and then I received a letter from my uncle Bob: “At last I’ve looked up some information about Philip Turnor,” he wrote. He had discovered Pearl Weston’s family history, Across the River, and sent me a few pages. At the beginning of her book is this wisp of a story passed down through six generations: “Our Grandma Campbell remembered, when a little girl, her grandfather, Joseph Turner, speaking about stories he’d heard of his Grandfather Philip Turnor travelling rivers in Northern Canada with only the stars to guide him.” Reading that passage, I began to imagine Turnor with his sextant, compass, and watch, and with his Cree guides and my great-great-great-great grandmother, surveying the rivers of Rupert’s Land. This started me on my own travels — to the Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, to the Orkney Islands, to England, to Moose Factory-to discover who Philip Turnor was and what he contributed to the surveying and mapping of Rupert’s Land, the territory that came to be the Canadian north.