In his 1998 book The Greatest Generation, American journalist Tom Brokaw introduced us to many who were raised during The Great Depression and later went to war, their only motivation being it was “the right thing to do.”

As the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month nears — with this year’s Remembrance Day commemoration marking the 100th anniversary of the armistice that ended the First World War — Brokaw’s conclusion that we will never again see the likes of that generation reminds us that we should, we must, pay attention to the words of those who walked that perilous walk while they are still here to share them.

But their number is quickly dwindling. For example, of the some 3,500 members of the 1st Battalion of the 9th Infantry Brigade of the 3rd Canadian Division that came ashore at Juno Beach in Normandy, France in June 1944 and proceeded to help liberate Nazi-occupied France and Holland, just two are still alive.

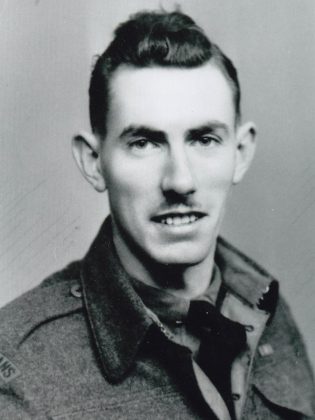

Don Fowler, a Peterborough native, lives in Brockville. Douro native Joseph Sullivan, 98, is much closer — a resident of Fairhaven whose fourth floor room, with its numerous wall-displayed certificates and commendations, speaks to the pride of the man who resides there.

“It was a great experience, I don’t regret a day of it,” says Sullivan, his memory of names, places, and events associated with his war experience as a member of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders nothing short of remarkably precise.

“But we were always scared. We were quite naive. We had no idea of what we were going to get into. Yes, I consider myself lucky. I was in three bad explosions and each time somebody beside me was killed. I had scratches and bruises, but I survived. It wasn’t my time.”

A carpenter by trade, Sullivan enlisted in 1941, trained in Kingston, Peterborough, and at Camp Borden near Barrie, and shipped to England in 1942. A radio operator when he waded ashore at Juno Beach two years later, he was just 23 years old.

What followed for Sullivan and his comrades was 56 days on the front line as they advanced through France into Holland. Come the war’s end in early May 1945, Sullivan et al were in the German port city of Emden.

Upon returning home in late December 1945, he returned to work as a carpenter. However, back problems took their toll. In 1967, he began a new career selling real estate for Bowes and Cocks, retiring in 1978.

While Sullivan has never returned to France, France has come to him.

In 2015, that country awarded him the rank of Knight of the French National Order of the Legion of Honour in recognition of his helping liberate the country from Nazi occupation.

This year, he has been invited to join the Consulate General of France in Toronto for a Remembrance event on November 14th, but he won’t be attending. More important to him is the Remembrance Day ceremony being held at Fairhaven.

“It’s quite an honour to be recognized … it makes me feel good,” says Sullivan who, just this past February, was presented with the Sovereign’s Medal For Volunteers by Governor General Julie Payette — “She’s quite a girl,” he says.

The award was granted in recognition of his efforts to ensure veterans’ sacrifices are never forgotten.

“A lot of remembrance is gone,” says Sullivan. “I don’t whose fault that is. Part of it is maybe our (veterans’) fault. When we came back from the war, we were finished with it. We didn’t want to affiliate ourselves with it anymore. It was the past. It was time to move on.”

Sullivan did venture to Holland in 2005 for the 60th anniversary of that country’s liberation. Earlier, working with Dutch officials, he played a role in the renaming of 11 streets in the city of Zutphen. Those streets now bear the names of 11 members of the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders who were killed in action there on April 4, 1945.

In Peterborough, Sullivan was also involved in the erecting of a memorial plaque in Confederation Park that honours the contributions of the Highlanders. And, of course, his own name is listed among the thousands of names on the Veterans Wall of Honour tucked in behind the Cenotaph.

“A lot of people don’t know why they’re wearing a poppy,” laments Sullivan. “It’s a decoration more than a remembrance. They don’t know the significance of it. Those that were killed beside me … I can see them. I see their faces every day, not just on Remembrance Day.”

While it would seem a man who has seen so much, and done more, would have no regrets, Sullivan has one.

“I never mastered public speaking. I’m okay talking, sitting here, but not in front of people. Over the years, I often wanted to go to schools to talk, but I didn’t because I felt I couldn’t. I wish I did that.”

Instead, Mr. Sullivan holds court at Fairhaven for anyone who wants to take the time to listen. Up until February 14, 2015 when she died, his wife Ella was also a resident at the long-term care home. Today he enjoys visits from their five children, seven grandchildren. and six great-grandchildren.

And, as he has done for years now, he boards a city bus pretty much every day and makes the trek to the Lansdowne Place Food Court where he enjoys lunch with friends. Inevitably, that conversation centres on world events — a topic which Sullivan has no shortage of opinions on.

“The world is headed for another war,” he says.

“Why can’t people live together peacefully? The Middle Eastern countries, they’re rich countries. The people are starving and they guys holding all the money do nothing. They could be living a good life. It doesn’t make sense.

“Until people can sit down and iron out their differences it’s going to be that way. War is terrible. Nobody wins. It’s ugly. A lot of young people didn’t come home. They can talk about the war to end all wars, but we haven’t got there yet.”

A lifelong reader, a copy of Mark Zuehlke’s Breakout From Juno: First Canadian Army and the Normandy Campaign, July 4 – August 21, 1944 sits on a tray table beside Sullivan’s easy chair. He references it as being an accurate narrative of Canadians’ huge role in the days that followed the D-Day landings.

Still, words on a page — while a valuable resource for generations to come — pale in comparison to the first-hand accounts offered by the likes of those who were there and fortunate to come home to live a full life.

“I am very fortunate,” acknowledges Sullivan, grateful not only for the years he has been granted but also for his being able to remember those years, and his varied experiences, with such clarity.

And like Brokaw, he agrees the world will never again see the likes of his generation.

“We knew we had a job to do and we didn’t question that. There were hard times but we got it done.”