While assuring she’s not an alarmist, Meagan Hennekam is, well, alarmed, and has been for quite some time now.

As executive director of Peterborough’s YES Shelter for Youth and Families, Hennekam has been, and remains, an up-close-and-personal witness to the devastating effects that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has had on homeless youths and families.

While it’s easy for most all of us to look the other way as we deal with our own issues around self-isolation and the pandemic’s effects on family life, income, and lifestyle, Hennekam doesn’t have the benefit of out-of-sight-out-of-mind. With the heightened struggles of the homeless in her face daily, the luxury of aloofness isn’t hers to enjoy.

“I don’t think I could have ever imagined a circumstance that could be much worse,” says Hennekam, now in her fourth year at the helm of the Brock Street YES shelter.

“Everyone is really tense. You can feel and see people’s frustration. There’s not anywhere near the same level of hope. Before COVID, about 85 per cent of youths experiencing homelessness would have some sort of severe mental health distress and 42 per cent would attempt suicide within the first year of being homeless. If they did the same study now, I can’t even imagine what it would tell us.”

That’s not to say there haven’t been studies done examining COVID’s impact on homeless and marginalized people. There have been several throughout the course of the pandemic including one published in January in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Conducted by the Lawson Research Institute and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, the study followed 30,000 people with a recent history of homelessness over a six-month period. Its central finding is they are 20 times more likely to test positive for COVID-19, 10 times more likely to develop complications and require intensive care, and five times more likely to die.

VIDEO: Mark Graham, Canadian Mental Health Association Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine Ridge

But as disturbing as that finding is, the pandemic’s impact on the already fragile mental state of homeless people is no less cause for concern. Few are as well aware of that as Mark Graham, the longtime chief executive officer of the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine Ridge.

“We know that the pandemic has widened mental health inequities, making things worse for those who were already vulnerable due to experiences of marginalization, including individuals who are homeless or have substance abuse issues,” says Graham, summarizing the findings of a 2020 nationwide survey on the pandemic’s mental health impacts undertaken jointly by the CMHA and researchers with the University of British Columbia.

In addition, says Graham, homeless people “have limited ability to prevent infection”, and their options are few in terms of accessing the health care they need should they test positive.

Over the last year CMHA’s Four County Crisis Line (705-745-6484) has seen a marked increase in the number of calls pertaining to a wide range of mental health issues. Graham says that’s going to be the norm for quite awhile going forward.

“We’re going to get more calls as things open up and people start readjusting to normalcy. People will all of a sudden realize ‘Oh my goodness, I didn’t realize it was this bad.’ When you’re in it, you struggle and manage through it. It isn’t until things get better that you realize how bad it was. It’s almost like PTSD.”

But at YES, Hennekam’s primary focus is on today, not tomorrow, starting with the shelter capacity’s having been reduced by one-third due to COVID restrictions — a challenge common to all shelters across Peterborough.

“For the first time in the last couple of years we’ve had to turn people away,” she says. “What we used to do in the past was tuck a cot in a corner or something like that. That’s not a good solution but it’s better than saying ‘Sorry’. We’re not allowed to do that now.”

And then there’s the inescapable fact that isolating is a much different animal for shelter clients than it is for most everyone else.

“All of us who have stayed home have the internet and the finances to order books and do whatever else we can do to stay busy — even those folks are feeling really isolated and their well-being has declined. The homeless were isolated before the pandemic. If you’re in the emergency shelter today, your options are to sit on a bunk bed with usually one other roommate, or be outside. And it’s been really cold.”

That, adds Hennekam, has resulted in a “pressure cooker” environment.

“We’ve seen a huge increase in suicide attempts in shelters, a really serious decline in people’s well-being, and behavioural outbursts that are not normal. They’re so unwell that there’s not the same level of control.”

Adding to the tension, says Hennekam, is heightened stress for shelter workers. She says when the adverse effects of the pandemic on frontline workers is referenced, shelter and social service outreach workers are rarely, if ever, mentioned.

“They (shelter staff) are here at 3 a.m. when clients are in some sort of crisis,” she explains. “Quite literally, there are moments when I’m working in my office and I can hear people screaming and crying. That used to happen some of the time but it’s almost a daily occurrence now. Our staff try to calm them down and give hope but it’s really hard on them.”

As chief executive officer of the United Way Peterborough and District, Jim Russell is the public face of what is a five-year $5 million fundraising campaign for 19 agencies serving the city and county, YES among them. He says the pandemic has served as “an amplifier of underlying issues that exist.”

“We have this whole hashtag unignorable campaign around homelessness, around mental health, around addictions, around domestic violence, around unemployment and income. For us the danger (of the pandemic) is we’ll forget about those things. What we have learned is those things have only been exacerbated.”

“I think this time has really helped us recognize that we’re all the same. We all have the same desires. We desire community. We desire love. We desire respect. That we need to extend all that to people who are vulnerable and certainly those that are homeless. My hope is coming out of this there’s a more inclusive sense of what community is and can be.”

“We can’t un-know what we know now as a result of coming through COVID times. We have to think strategically. We have to invest money. We have to understand that for people to be safe from COVID in the future they need to be housed.”

Russell wholly shares Hennekam’s concerns about the impact on those who work to ease the lot of the homeless.

“Shelter staff are making minimum wage, maybe a bit more,” he notes.

“We tend to demean people that are making a minimum wage, not a living wage. What COVID has done, I hope, has help us recognize other positions that might not be seen as professional but are certainly just as necessary in terms of meeting people’s needs.”

Not unlike her counterparts at dozens of social service agencies and service locations across the region, Hennekam is “particularly concerned” about the level of funding support that will come from governments dealing with the hangover of COVID-19 relief spending and looking to make spending cuts.

Noting that 85 per cent of Peterborough’s emergency shelter program is funded by the municipality, Hennekam says fundraising is relied on to make up the difference, but adds raising awareness of the growing need for more shelter space and affordable housing is no less important moving forward.

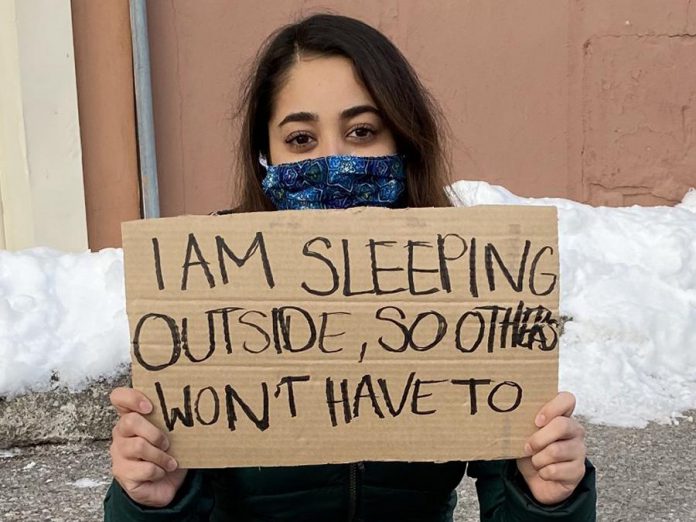

Enter Simal Iftikhar. On Friday, March 26th into Saturday, March 27th, the Trent University student will sleep outside in Peterborough to raise funds for YES, as well as to bring awareness to the daily experience of Peterborough’s homeless.

To date, her modest goal of $1,500 has been surpassed by $700 as other Trent students and some co-workers of hers have also signed on to sleep outside the same night and morning. To donate, visit canadahelps.org/en/pages/virtual-sleep-out/

“A big roadblock is the stigma around homelessness,” says Iftikhar, who helped establish a walk-in clinic at a local agency and who now works in the mental health field.

“Unless you educate yourself, it is easy to walk to the other side of the street. A lot of times all they (homeless people) are looking for is a conversation. We don’t stop anymore to say ‘Hello’. We have assumptions and stereotypes of things we think are going to happen if we associate ourselves with anyone who is homeless.”

Iftikhar says that during the pandemic, homelessness has become “a crisis within a crisis.”

“The homeless don’t have the proper PPE. They don’t have transportation to take them to screenings and tests. And there is less available programming like drop-in programs they can access.”

When all is said and done, she says her sleep-out fundraiser, which is part of the annual Peterborough Cares initiative, is really all about walking a mile in the shoes of homeless people.

“When we wake up in the morning, we’ll be alone,” Iftikhar says of her virtual sleep out. “That is how they feel every day.”

This story has been corrected. Simal Iftikhar’s sleep-out event will take place in Peterborough, not Ajax, and the pre-COVID suicide rate for homeless youth is 42 per cent, not 92 per cent.