It will first present itself as a headache.

Depending on the severity, nausea or vomiting will follow, along with dizziness, a heightened sensitivity to light or noise, and an inability to concentrate, quite possibly leading to confusion and memory lapses.

Widely known as the invisible injury, a concussion is not to be taken lightly. As a traumatic brain injury caused by a blow to the head, the effects can be long lasting and, in severe cases, fatal.

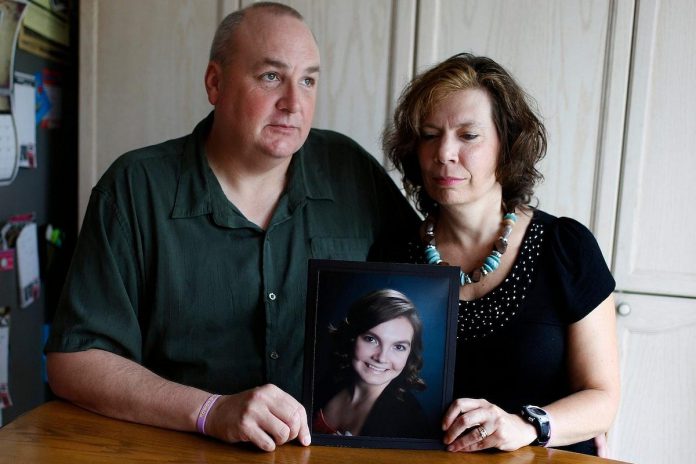

On May 8, 2013 in Ottawa, the captain of the John McRae High School girls’ rugby team was tackled and upended before landing hard on her head. Despite quick on-field medical attention and excellent post-injury care at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Rowan Stringer died four days later. She was 17 years old.

A 2015 coroner’s inquest into Stringer’s death determined the cause to be Second Impact Syndrome (SIS). Evidence revealed that Stringer had texted to a friend that she had sustained blows to the head during earlier rugby games on May 3 and 6. Despite suffering headaches, and having searched ‘concussion’ on Google, Stringer messaged her friend that she would continue play the sport she loves, writing ‘Nothing can stop meeee! Unless I’m dead.’

The tragedy of Stringer’s death can’t be overstated. It was preventable. Had she not returned to play after those first blows to the head, she would still be alive today, having graduated from Ottawa University to which she had already been accepted, and working as a nurse.

If Ryan Sutton considers himself lucky, he isn’t saying. That said, it’s not lost on him that any one of the eight concussions he has sustained — four by the time he graduated high school — could have left him permanently disabled, or worse. Now, as project manager of Peterborough Area Concussion Awareness (PACA), Sutton’s personal experience “fuels” his work increasing education on the signs of concussion and, more vitally, the importance of allotting time to heal.

In 2018, Rowan’s Law was passed by the Ontario legislature, making it mandatory for sports organizations to ensure athletes under 26 years of age, parents of athletes under age 18, and coaches, team trainers, and officials confirm they have reviewed Ontario’s Concussion Awareness Resources module. In addition, leagues must put in place a Concussion Code of Conduct that lays out rules supporting concussion prevention, and establish Removal-From-Sport and Return-To-Sport protocols.

With the last Wednesday of each September designated Rowan’s Law Day, PACA will mark September 28th in a significant way, premiering at www.paca.health a series of videos highlighting four critical aspects of concussion: Recognize, Remove, Manage, and Prevent.

VIDEO: Recognize, Remove, Manage, Prevent – Docuseries Trailer

Shot mostly in Peterborough, the hour-long four-part video series was produced by Sutton with his university friend (and equally passionate concussion awareness advocate) Seth Mendelsohn contributing as a story creator and editor.

Featuring a combined 19 interviews, the series aims to influence local, provincial, and national sports organizations to take concussion more seriously by implementing policies and strategies aimed not only at early recognition of the symptoms but also the removal of athletes from play until it’s safe for them to return.

“The video series shows how all the stakeholders — teammates, coaches, parents, and teachers — can support one another and how important that is to someone who’s going through a concussion experience,” says Sutton, mindful of the difference that such awareness and protocols could have made for Rowan Stringer.

“One of the things we really try to address is the teammate and the friend have the ability to help that (concussed) individual and speak on their behalf,” adds Mendelsohn.

“It’s hard to explain what you’re going through (when concussed). It’s hard to identify. There are a lot of challenges that happen when you experience the injury. Having a person who’s a bit more educated on the severity can break down some of those walls.”

Sutton notes many concussed athletes go through “an internal negotiation” following their injury, asking themselves ‘Should I play? Should I not play?’

“When the stakes are high, more often than not athletes will continue to play,” says Sutton, who played hockey, baseball, and rugby as a youth growing up in Peterborough.

Mendelsohn, who was raised in Markham, played high school football in Vaughan. He suffered his only diagnosed concussion in Grade 12, a week before the season started.

“I was able to get back to class pretty quickly, but it took me four to six weeks to get back to football,” he recalls. “A lot of my teammates were also my classmates. They didn’t really understand why I wasn’t able to play if I was in class.”

“It was very alienating and it led to mental health complications that I didn’t acknowledge at the time. It was hard to correlate the head injury with the anxiety. When I met Ryan, we were able to connect about our experiences. I’ve learned a lot more through this journey that we’ve been on.”

Mendelsohn and Sutton met at Brock University, teaming up to co-found the HeadsUp Concussion Advocacy Network in 2017 with the mission “to build collaborative networks and partnerships that work to innovate concussion education, research and awareness.” Sutton, meanwhile, wrote his Masters thesis on The Sport Related Concussion Experience. A few years later, in his role at PACA, he connected with Mendelsohn to continue the work they started and remain passionate about.

“We’ve been on a journey to essentially get to where we’re at right now,” says Sutton, noting he’s confident more communities will “take notice of the work we’re doing at a local level” and be inspired to do likewise.

While Mendelsohn agrees there’s much work to still be done around concussion awareness, management and prevention, he’s heartened by the progress seen since Rowan Stringer’s tragic death.

“Ryan and I have talked at a few high schools and seen that Rowan’s Law Day is such a big thing for them — they all wear purple, they all have their own way of addressing this,” he says.

“What I don’t think people really understand is the youth concussion rate has constantly risen since 2010. This is an ongoing issue but we are seeing a lot more education, with a lot more people realizing that this is something that needs to be talked about.”

Both agree that the example being set by professional sports leagues in the form of players being removed from the game if they suffer a head hit is a good thing in terms of its influence on lower-level sports organizations.

“Whatever they see on TV, whatever they’re seeing live at a pro game, they’re going to start to emulate,” says Ryan, adding “More rigid removal from playing is very important. It’s going to trickle down.”

Still, personal experience is the best teacher, and for both Sutton and Mendelsohn, it’s the driver of all they do and plan to do.

“I felt really strange when I was going through my recovery in terms of how I was perceived,” says Sutton.

“I’m a big advocate of understanding the social side of the injury. We know a lot about the medical side, but not how it’s intertwined with mental health. I’m very passionate about helping others not go through what I went through or, if they do, have resources available to them that will make them feel like they’re not alone.”

To view the PACA concussion education documentary series, visit www.paca.health.

This branded editorial was created in partnership with GPHSF, Your Family Health Team Foundation. If your organization or business is interested in a branded editorial, contact us.