Plastic-Free July is a month-long global movement that activates millions of people to be part of the solution to plastic pollution. GreenUP is shining a light on ‘greenwashing’ with this article, to raise awareness of the power of market research so that consumers like you and I can reduce our plastic waste and make better purchasing decisions.

Greenwashing is no joke, and yet it’s an old joke! The term is thought to have come from the 1980s and transformed the way customers chose their products. Over time, this term began to be known by the public as an understanding of the environmental impact a business or its products communicates to its customers.

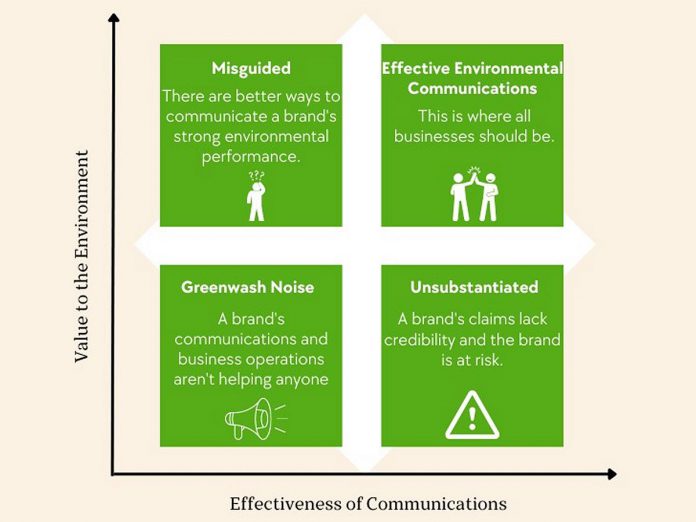

Greenwashed businesses or products are, to most of us, those lacking accountability for their own environmental impact. By choosing to communicate their impact using appealing marketing strategies, businesses can mislead customers into thinking their products have a lower environmental footprint.

If there is anything that customers can do as they move towards making better purchasing decisions, it’s to keep a close eye on greenwashing. If a product sounds too good to be true, it may be.

Greenwashing can come in many forms:

- Symbolism. When products use symbolism on their packaging — like green leaves on dish soap or a recycling symbol on laundry detergent — it can distract from a product’s actual impact, how much pollution is created in its production, packaging and distribution, or what ingredients it contains. There is power in imagery.

- A product’s trade-offs can be hidden. While the intent of purchasing reusable bags at a grocery store can be a valuable switch from using plastic bags, does the same apply if you purchase one every time or if you consider what the reusable bags are made of?

- Lack of proof or certification. A lack of proof or certification allows marketing strategies to fall through the cracks and appeal to the customer who may not have time to do market research. The term ‘eco-friendly’, as an example, can be used as a false certification.

- Selective disclosure. Selective disclosure is a form of greenwashing where companies may shine a light on some good practices, while shying away from other practices that may negatively impact the environment. Think of a business replacing their single-use plastic straws with drinking caps that use more plastic.

It is both up to consumers like you and me, as well as people who handle communications and purchasing for businesses, to work together to address greenwashing and to identify and influence what sustainable products can be found in the community.

Eileen Kimmett is GreenUP’s Store & Resource Centre Coordinator. She oversees sourcing products that are environmentally and socially responsible. For Kimmett, the success of the GreenUP Store as a trusted resource can be attributed to the two-way relationship between customers and the store.

“We often learn of great and trusted products from our customers,” says Kimmett. “One told us of an Ontario-based laundry soap company that takes back and reuses their bulk containers. When we hear about a new product line like that, one that can reduce plastic waste and emissions due to transportation, we are quick to jump and make that product available to our customers.”

Kimmett recommends that any individual looking into new household products do research into local stores that are transparent about their products, the ingredients’ list, and how they reduce environmental impact.

“Before I stock any product at the GreenUP Store & Resource Centre, I think to myself, ‘How does this play a role in creating an environmentally healthy community?’,” Kimmett explains. “I also conduct extensive research into a business’s accreditations, packaging, reviews and ratings, and even seek out a contact before committing to the product.”

While it is the responsibility of stores like GreenUP to do the good work to research their products, it may not be within the capacity of others to do the same. Mindful shopping can help customers find products that are clear about their impact.

And, as Lydia Noyes from EcoWatch says in A Guide to GreenWashing and How to Spot It, “Not all companies practice greenwashing maliciously. Often, it’s as much a misunderstanding on the marketers’ end as it is for customers.”

In fact, in a 2016 study from Cornell University, it was found that businesses often feel pressure to report their environmental impact, leading them to hastily communicate their practices without disclosing accurate information.

Customers are responsible for understanding their purchasing power, but it can take time.

Here’s a challenge to help identify greenwashing tactics: next time you are grocery shopping, pick up one item and look at the product label in great detail.

Does it have symbolism? Certifications? Does it make great claims for some benefits, and not others?

By thinking carefully about what you buy, you will gain confidence that your purchases are more green and less greenwashed.