In a world where taking even a year-long hiatus justifies a new commercial product as being a comeback, the creators of the second-most technologically influential franchise in the history of film (The Matrix trilogy) had a lot to prove.

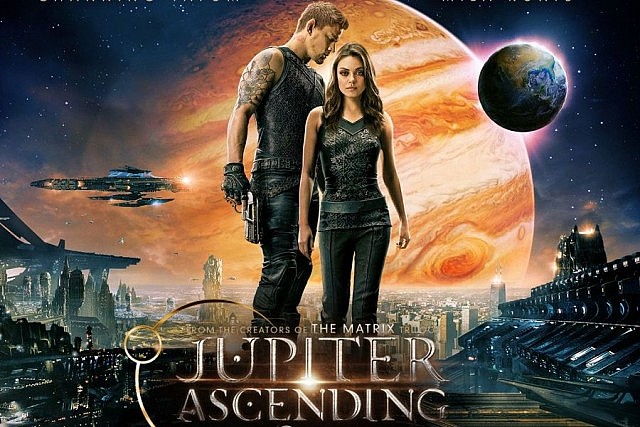

Like a pop star with a tanked record, many have viewed Jupiter Ascending as a make-or-break moment for sibling writing and directing team Andy and Lana Wachowski (formerly the Wachowski Brothers). So why so little fanfare this time around?

At the very least, this muddled incoherent film aims to celebrate the latent abilities and power of its female protagonist, as opposed to rival fantasy film The Seventh Son which seeks to morally and literally burn them alive.

The “plot” concerns a trans-dimensional reality that secretly intermingles with our own, where Earth is viewed as little more that a vast colony of livestock to be harvested as intergalactic makeup. Think second-rate The Matrix crop fields. Though here the end product matches the gaudy veneer of the immortal elite and replaces the biomechanical grittiness of its superior predecessor.

Humanity and myriad other unseen species throughout the universe have been artificially planted to dwell in ignorant bliss until they achieve a level of Darwinian perfection, at which point they are reduced to a eternal youth serum. The queen of the all-conquering House of Abrasax — a gilded dynasty of glamorous sadists — mysteriously dies, leaving her three vainglorious children squabbling over their vast celestial inheritance.

Meanwhile, an apathetic janitor named Jupiter Jones (Mila Kunis, as effervescent and likeable as ever) churns through her perceived working-class misery, unaware that her incredibly rare genetic code certifies her as a earthbound duplicate of the deceased queen and heir to the coveted human home world. The perfection of genes has a near-spiritual quality to the aliens which, when aligned properly, bestow a fortunate being with a sense of reincarnation.

The depiction of Jupiter’s life as a child of immigrants in servitude is thoroughly condescending. The positions may seem menial but if there is one lesson essentially every North American needs to learn, it is to not victimize people.

A beautiful sequence in a dilapidated country home shows Jupiter accented by swarms of bees that act as an extension of her body. Bees, we are told, are genetically designed to recognize royalty.

Balem, the eldest Abrasax (Eddie Redmayne giving us hushed Ralph Fiennes as a freckled, porcelain Dior faerie) puts a bounty on Jupiter’s naive head to assure his claim to Earth. Enter Caine Wise (a smouldering Channing Tatum in full-on Falcor luck dragon drag) to save our titular damsel from squealing green-screened attackers. Woof.

The man may be leading the way and calling the shots, but he’s also wearing all the makeup. Though it’s difficult not to roll your eyes at Kunis receiving second billing to Tatum despite so definitively playing the main role. No matter how a film is executed, flagrantly sexist marketing campaigns are alive and well.

Wise’s anti-gravity boots propel the gormless duo into a spectacular dogfight that eviscerates the Chicago skyline. Even if the gimmick is hammered home a half-dozen times too many, moments like this remind us that the Wachowski siblings still have their touch. Yet one can’t help but feel that the original The Matrix is the best work they’ll ever realize.

It’s a shame that their signature oil-slick compositions found so prevalently in Bound and The Matrix have become so deeply buried under stunning but utterly anonymous CGI. The busy visuals suggest Bosch’s idea of hell: you’re never quite sure where to look.

The initial 20 minutes careen so carelessly between over-designed scenarios that it will take you half of the film to decipher what feels like a 15-page script. The execution in virtually every department has been realized in an exceptionally disappointing manner.

But the ideas shine through the kaleidoscopic frenzy. A simple initial rhetoric about seeing the best in people while expecting the worst rings true. Like so many New Age concepts and practices, self-actualization is deservedly front and centre. After all, “I can” and “icon” are only two letters apart.

It is repeated throughout the narrative that time is the ultimate commodity. Similarly to the Wachowskis’ sprawling yet largely derided Cloud Atlas, Jupiter Ascending ruminates heavily on how our lives are forged by our own decisions and not explicitly by our surroundings.

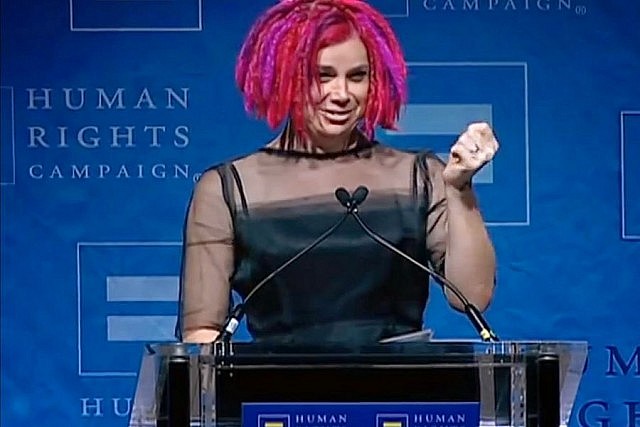

Rather than seeing the film as a thin parable for steamrolling contemporary consumerist culture, I can’t help but picture co-director Lana (born Laurence) Wachowski’s very public transition as a transwoman. Her remarkable speech for the Human Rights Campaign which celebrated her contribution to trans visibility was itself an act of courageous visibility.

An initially dull chapter of the film, where Jupiter seeks to have her proper royal title engraved on her persona, brings a lump to the throat when one considers the personal insight that screenwriter and director Wakowski brought to it — the laborious process of earning and acquiring your preferred pronouns.

The unfamiliar is frightening to many and the blurring of sedentary gender binaries can create a near-toxic shock for those accustomed to the template of Lumbersexuals and Victoria’s Secret archetypes. But really, these illusions are just that; little more that hyper-real marketing campaigns.

The current importance of trans visibility cannot be understated. The media engagement of Lana Wakowski and Laverne Cox may engage their personal struggles but they, like Rock Hudson before them, put a human face on a terribly stigmatized group.

Jupiter Ascending says one thing and says it loud and clear: “I wish better for you. I wish for you the life you’ve always wanted.”