To say this has been quite a week for those who hold close in their hearts the memory of Chanie Wenjack would be an understatement.

Just days after the federal Liberals earmarked $5 million for The Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Fund, Trent University officially launched the Chanie Wenjack School for Indigenous Studies.

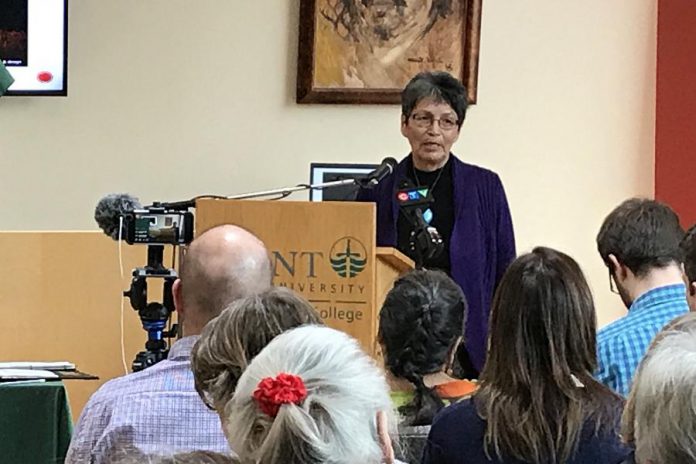

In doing so, the university ensured the participation of key figures in the movement struck in his name, among them Wenjack’s sisters Pearl Achneepineskum, Daisy Munroe and Evelyn Baxter, as well as Downie’s brothers Mike and Patrick.

On October 16, 1966, Wenjack, 12, left Kenora’s Cecillia Jeffrey Indian Residential School, intent on returning to his home of Ogoki Post, some 600 kilometres away. Six days later, the Anishinaabe youth’s body was found near Farlane, the cause of death determined to be exposure combined with hunger.

Wenjack’s story was the inspiration for the album The Secret Path released by the late Gord Downie in 2016. That same year saw the establishment of The Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack Fund, the goal of which is to further and assist Canada’s ongoing reconciliation with Indigenous people over past mistreatment and abuse, including the establishment of government-sponsored residential schools established to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture.

“I don’t think Chanie ever thought of anybody ever honouring him … He was just a little Indian boy,” said Achneepineskum.

“I prayed before I came that this would be a good day. Even though Chanie is not here, our brothers Mike and Patrick are here. I’m pretty sure Gord is here with us as well.”

The Chanie Wenjack School for Indigenous Studies — the naming was first announced last June on National Aboriginal Day — brings together Trent’s undergraduate, masters and PhD programs under one umbrella, uniting events, initiatives and spaces dedicated to Indigenous perspectives, knowledge and culture at the university.

As noted by Professor David Newhouse, the school’s director, the naming continues a long and proud tradition of closely aligning the university with Indigenous peoples and their culture.

Back in 1973, Trent paid tribute to Wenjack, and all residential school victims and survivors, by naming its largest lecture space The Wenjack Theatre. But long before that, Trent became the first university in Canada to establish an academic department dedicated to the study of Indigenous peoples and knowledge.

“Our goal in creating this school is to work to ensure the difficult past that we know about is not repeated,” said Dr. Newhouse. “The school is not a building. The school is all of the people who work here – the faculty, the staff and the students. We are the school. We will continue and it will change and morph over the centuries to come.

“Chanie Wenjack is a powerful symbol of our hope. We focus not on what Chanie was running from but what he was walking toward. He was determined to get home to a place of safety, respect, dignity and love. Our efforts are dedicated to fostering these places for Indigenous people within Canadian society.”

While declining to be interviewed by media gathered for the event, Mike Downie, in the event media release, praised Trent as “a leader in Indigenous education that breaks down barriers between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians through its programming, resources and initiatives.”

Also taking to the podium were fourth-year Indigenous Studies student and former Trent University Native Association president Joy Davis, and university president Dr. Leo Groarke who heaped praise on Dr. Newhouse’s role in the school’s naming.

“We’re a university so we make it very challenging to develop any new initiative,” said Dr. Groarke, tongue in cheek.

“It requires talk to the extent you wouldn’t believe if you’re outside the university community. Many committees, all sorts of levels of approval. It was really David’s shepherding this proposal through all the discussions … that’s really been a key force to making this happen.”

Earlier, prior to the formal proceedings, Achneepineskum reflected on the week, which started with the federal budget injection of $5 million into the fund dedicated to continuing the conversation that began with Wenjack’s residential school experience and subsequent tragic outcome.

“It took me a few notches down when I heard that … I was in tears,” she said. “I don’t know what five million is. All I can think of is a thousand dollars. It’s got to be a lot of money. It’s going to help all the children we’re thinking about.

“I’m glad that they (federal politicians) finally found out that we exist and that we matter like everybody else. It’s long overdue.”

In addition to the school’s naming, it’s now mandatory at Trent that all undergraduate students successfully complete at least half a credit from an approved list of courses featuring Indigenous content. Trent is just the third Canadian university to make that a mandatory requirement.

Meanwhile, this weekend (March 3 and 4), at 8 p.m., ‘Chanie’s Life – His Courage, Our Challenge’ will be presented at Nozhem First Peoples Performance Space at Trent University.

Presented by the Indigenous Performance Studies Program, in conjunction with the 41st Elders Gathering, First Peoples House of Learning and Trent’s Indigenous Studies Department, the program brings together film, dance and song to shed light on Chanie’s journey from his home to the residential school and his tragic attempt to return home.

The story of Chanie Wenjack

In the fall of 1963, Chanie Wenjack was taken away from his family — his parents, sisters, and two dogs — at Ogoki Post on the Marten Falls First Nation in northern Ontarioand forced to live 600 kilometres away at the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario.

The Anishinaabe boy was only nine years old and understood very little English. Around 150 other Indigenous children lived at the school, which was run by the Women’s Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church in Canada and paid for by the federal government.

The children lived at Cecilia Jeffrey and attended classes at schools in Kenora. Chanie (who was misnamed Charlie by his teachers) struggled to learn English and arithmetic and had to take remedial classes.

Chanie had previously never tried to run away from the school but, after three years, he had had enough. On Sunday, October 16, 1966, Chanie and two of his friends, brothers Ralph and Jackie MacDonald, decided to leave. Chanie told his friends he wanted to see his father.

It was a sunny and mild afternoon, so the three boys left wearing only light clothing. They travelled north through the bush using a “secret path” known to children at the school. They headed for Redditt, a railroad stop 32 kilometres north of Kenora and 48 kilometres east of the Manitoba border.

They had to stop frequently as Chanie was in poor health (a post-mortem would show his lungs were infected at the time of his death). While they were walking, Chanie found a CNR schedule with a route map in it — but he didn’t know enough English to read it.

VIDEO: Heritage Minutes – Chanie Wenjack

More than eight hours later, the boys arrived in Reditt. A local white man the MacDonald brothers knew took the exhausted boys in for the night. Early the next morning, the boys walked a short distance further to the cabin of Charles Kelly, an uncle of the Macdonald brothers, who let them stay.

Later that same morning, Chanie’s best friend (who had also run away from the school and was another of Kelly’s nephews) showed up. Among this family reunion, Chanie was considered “the stranger”.

On Thursday, Kelly took his nephews up to his trapline by canoe, leaving “the stranger” behind. Chanie told Kelly’s wife he was going to walk the five kilometres to the trapline, and she gave him some matches in a little glass jar and some food.

Chanie made it to the trapline and stayed overnight but, after Kelly told him he’d have to walk back to Redditt, Chanie said he was going to walk home instead. Kelly showed him how to get to the railroad tracks and told him to ask railroad workers along the way for food.

Over the next 36 hours, Chanie attempted to walk the almost 600 kilometres home. All he was wearing was a cotton windbreaker while he faced weather that included snow squalls, freezing rain, and temperatures between –1° and –6° C. He only managed to walk 19 kilometres before dying from exposure.

When a railway engineer found Chanie’s body, he was lying on his back in soaked clothing and had bruises on his shins and forehead, presumably from falling.