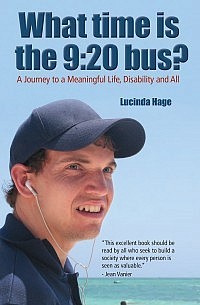

Local author Lucinda Hage has released a non-fiction book entitled What Time is the 9:20 Bus? A Journey to a Meaningful Life, Disability and All — the first book of its kind in Canada. There are hundreds of books about children with disabilities, but none about their successful transition to adulthood.

Unable to have her own child and anxious to adopt, Lucinda is overjoyed when a newborn baby is granted to her and her husband. Devastation follows when the baby, Paul, is diagnosed with a serious genetic disorder that means he will be intellectually challenged and require medical intervention for the rest of his life. Lucinda’s already-tenuous marriage disintegrates, and she becomes a single mother caring for a difficult and fragile child.

With exceptional resilience, tenacity, faith, and very hard work, she makes a successful life not just for herself but for her son. Summer camp changes Paul’s life, and Lucinda finds a new partner and love. The reader cheers for Paul as he struggles to take his rightful place in society, and for his mother as she works ceaselessly to make that possible. At the end of the book, it is nothing less than miraculous that Paul, at 27, is living in his own apartment in Peterborough and takes the bus independently to his part-time job at the Holiday Inn.

About the author

Lucinda Hage was born in Calgary and moved to Peterborough to attend Trent University. She subsequently earned an MEd in Adult Education and Counselling from the University of Toronto (OISE). For 40 years, Lucinda has been encouraging others to achieve their potential through her roles as educator, counsellor, motivational speaker, workshop leader, advocate, and mother. Lucinda lives in Peterborough with her husband Murray Leadbeater, where they enjoy canoeing, cycling, and hiking in the summer, and cross country skiing and sitting by the fire in the winter.

Where to buy the book

What Time is the 9:20 Bus? A Journey to a Meaningful Life, Disability and All is available online at www.inclusionforlife.com, at Community Living Peterborough (223 Aylmer St. N., Peterborough, 705-743-2411), Five Counties Children’s Centre (872 Dutton Rd., Peterborough, 705-748-2221), Shish Kabob Hut (220 King St, Peterborough, 705-745-3260), and Happenstance Books (44 Queen, Lakefield, 705-652-7535). Fifteen per cent of all local book sales will go to Community Living Peterborough’s “A Home of our Own” Campaign.

An excerpt from What Time is the 9:20 Bus? A Journey to a Meaningful Life, Disability and All

Paul and I arrived at Wanakita along with a hundred other campers, their parents, brothers and sisters, family dogs, and piles of luggage. Some of the duffle bags were so heavy, kids had to drag them. What did they have in there — lawnmowers? If so, they’d better watch out for Paul.

“There’s Mike!” Paul shouted. Mike wound his way through the throng of people and gear and clapped Paul on the back. “How’s it going, buddy? Are you ready for camp?”

Then, in a moment I will never forget, Paul picked up his sleeping bag, looked up at Mike and took his hand. “Bye Mom,” he said.

The two of them headed across the recreation area, Mike’s big hand surrounding Paul’s. I watched him go until he was out of sight. Paul never looked back.

Tears were still spilling down my cheeks when I went into the administration building to use the phone. “Don’t worry, he’ll be fine,” the receptionist assured me.

“Oh, I know,” I replied blowing my nose. “Make no mistake, I’m not sad. These are tears of joy.” Paul had done it — all by himself.

The following summer, Paul returned to Wanakita for a two-week session. When I picked him up, I asked his counsellor, “How much did you tell the other kids about Paul’s medical and learning problems?”

“Not much,” he replied, “basically, we just had fun. The kids in his cabin were great; if Paul was a bit slower, they waited for him to catch up.”

Paul had been truly integrated. He had slept in a cabin and under the stars, walked the trails, canoed, roasted s’mores over the campfire, sung camp songs and swum in the lake.

For the first time ever, Paul was treated like a regular kid, not like a kid with a disability. His role models were campers and well-trained counsellors who accepted and valued him for who he was. Trust was built into every aspect of camp life, and it wasn’t long before Paul put complete confidence in the counsellors and the camp experience, and so did I. Every summer, and some March breaks in between, Paul continued to go to YMCA Wanakita — a place where he belonged.

Paul’s experience at camp helped me to see him differently. If he could handle being away from home for two weeks with typical kids — children without disabilities — then there was a lot more he could do. It deepened my resolve to help Paul achieve his potential, whatever that may be.

In the fall, Paul was moved to his third elementary school. His new teacher tried her best to understand him, and in her mid-term report said, “Paul is a delightful student who always brings an element of surprise and wonder to each day … he is exceptionally well mannered on all outings.”

During sharing time in class, however, Paul was reluctant to talk, unless his teacher asked him about lawnmowers. Then he would come to life and talk about “Pau cutty grass,” the “da green lawnmore” and the sound the engine made when “Mommy pu da chord.”

Paul may not have been able to speak clearly, but everyone understood him when he said, “Preese, Thank you, You’re welcon” or “Bress you,” when someone sneezed. Those simple words were a bridge that connected people to Paul and his world. And he was grateful even in the most unlikely situations.

After a blood test, as the technician put a band-aid on his vein, Paul would look up at her and say, “Thank you laydee.” Inevitably, the technician would turn to him, smile pleasantly and say, “You’re most welcome, Paul.” He loved this reaction, so he said “Thank you laydee” a lot. The 16-year-old girl at the check-out counter, however, was never quite sure how to respond.

Paul wasn’t afraid to ask for a hug from someone he knew and often said, “Hug me prease.” This was sometimes disconcerting. Paul drooled, and there was usually a sodden handkerchief around his neck. Nevertheless, this was a sign that he wanted physical contact with others — a positive sign for a young boy with many of the characteristics of autism.

It was 1997, the summer of good things. Paul’s neurologist put him on newly approved anti-convulsant medication and the results were amazing. For the first time in a long time, Paul’s seizures were controlled. What I had wished for, if I was absolutely certain I would get it, had come true. A soft cloud floated in my chest, and on top of it was a whiff of happiness.

It was time to think about me.